Digital Cultural Communication:

Enabling new media and co-creation in South-East Asia

Angelina Russo and Jerry Watkins

Queensland University of Technology, Australia

ABSTRACT

Digital Cultural Communication (DCC) is a new field of research and design which seeks to build a co-creative relationship between the cultural institution and the community by using new media to produce audience-focused cultural interactive experiences (Russo and Watkins 2005). By situating the development of cultural communities within DCC, the institution adopts a more representative curatorial practice and benefits through the creation of original community-derived content which can form new digital collections. The community benefits through improved 'information literacy' – the skills required to use digital technologies to engage in both cultural consumption and production (Russo and Watkins 2004) – and can go beyond being a stakeholder of an institutional exhibition. Information literacy skills enable the community to both produce and consume its own original cultural content, in the form of narratives, wikis, blogs, vlogs or any other medium which is supported by the institution and connects to the audience. The institution ceases to be the sole custodian of cultural experience; instead it provides co-creative infrastructure for the community and distributes original cultural content to the audience via multiple platforms – physical, online and broadcast.

This article uses a number of examples from around Asia to demonstrate how individuals and communities can benefit from the economy and immediacy offered by new media to co-create and distribute distinctive cultural content to broader audiences.

Keywords: Digital Cultural Communication; community co-creation; information literacy; new media.

INTRODUCTION

Digital Cultural Communication came about due to the evolution of Virtual Heritage, a field which began ten years ago. Virtual Heritage describes tangible elements of the built environment and has been dominated by researchers undertaking cutting-edge visualization, augmented reality and digitization projects. Virtual Heritage has been less focused on the social and cultural opportunities which new media affords communities and the opportunities for new audiences to be developed as a result of increased cultural representation (Forte 2005). For the most part, this mission tends to focus on tools and methods for representing inaccessible historic sites and whilst Virtual Heritage has broadened access to such sites, the field has often transferred the linear curatorial communication model of the modern cultural institution into the online environment. As a result, Virtual Heritage has not enjoyed widespread success with respect to the creation of cultural e-communities.

This is not necessarily surprising given that in the late twentieth and early twenty first century, the development of a critical mass of media and their impact on society presented such complex institutional challenges, particularly in cultural institutions. The rise of social communication has been pre-empted by the mutual remediation of telephone, television and computer (Bolter and Grusin 2001, p.224). In that light, community co-creation could be considered the convergence of memory, community, narrative and interaction. As audiences are given agency, their experiences with the interfaces of new media achieve new forms of interaction with the virtualized and dematerialized physical world. Community co-creation provides audiences with an agency where their individual experiences can bring together the social communication which relays the connections between memory, community, narrative and interaction. New media were defined as those forms which combined computing, communications and content through the process of convergence. While some of the questions of new media revolved around opportunities in representation - hence the rise of visualization - the contribution of new media would become their ability to produce new and otherwise unrealizable outcomes for social communication (Flew 2002, p.9-12).

DIGITAL CULTURAL COMMUNICATION

Shifts in entertainment and cultural tourism continue to impact upon the cultural sector. Global access to mass broadcast media; cyberspace and virtual reality technologies; video and interactive games, mobile technologies, the web, synchronous and asynchronous communication increasingly play significant roles in the consumption of cultural media. While these technologically based media continue to proliferate, 'site-specific' experiences which resemble museums - for instance, interpretive centers and theme parks - present challenges to the ways in which the museum and its audience conceptualize their experiences. These media use immersion in technology in an abstracted way by using mediated realities as a mechanism for drawing audiences into their knowledge base.

As both Bukatman and Morse suggest, less information comes to us via sensory, bodily experience while far more arrives in mediated, representational forms: "The relation between visual experience and cognition then...becomes increasingly crucial as a means of understanding the places available to the subject in this heavily technologized and electronically mediated culture" (Bukatman 1995, p.258). The separation of the visual and the haptic can sometimes result in an over-emphasis on the former: "visually based toys, displays and environments appeared, as if to compensate for the diminished role played by the senses" (Bukatman 1995, p.259). Although vision becomes detached from the body, it is reattached to an illusory body, that being the figure at the centre of the immersive experience - the one who enjoys the view.

The challenge for the contemporary cultural institution and one which is addressed by Digital Cultural Communication is to ensure that cultural content is not abandoned and that the value and durability of context is presented as much as the artifact itself. One of the reasons that immersion can be so deceptive in the cultural environment is that it limits the possibility for communities to partner with institutions. While they are engaged in effective and immersive interaction, this replaces effective communication of values or intention on the part of the audience. Witcomb (1999, p.104) suggests that - increasingly - the museum's role is one of translator and mediator and proposes that it see itself as involved in the production of cultural identity.

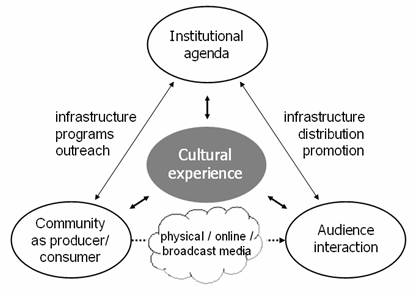

Digital Cultural Communication (DCC) examines relationships between cultural institutions, communities and audiences in order to create innovative cultural content by providing tools and methods for the design of compelling cultural interactive experiences across multiple platforms (physical, web, broadcast). The relationship between institution, e-community and audience can be illustrated by borrowing from Peirce's language of semiotics (in Mattleart and Mattleart 1998, p. 24). The community becomes the 'sign', the institution is the 'object of representation' and the audience becomes the 'interpretant'. Cultural 'experience' is a relative construct of the triadic relationship between these entities, represented in figure 1. By using the semiotic structure, we can re-appraise the role of the community in cultural communication. The community can go beyond being a stakeholder of an institutional exhibition: new media and information literacy allows the community to both produce and consume its own original cultural content, in the form of narratives, wikis, blogs, vlogs or any other medium which is supported by the institution and connects to the audience. The institution ceases to be the sole custodian of cultural experience; instead it provides co-creative infrastructure for the community and distributes original cultural content to the audience via multiple platforms – physical, online and broadcast.

Figure 1: Semiotic representation of cultural experience as a construct of the triadic relationship between community, institution and audience.

This semiotic model of the institution-community-audience relationship is a virtuous one to the extent that all parties benefit. The institution achieves community engagement as well as original cultural content to offer to a more distributed audience across multiple platforms. The community benefits from information literacy training by the institution, as well as a platform and audience for co-creative production. The audience has access to new and innovative cultural experiences co-created by the institution and community.

Knowledge Transmission vs. Digital Cultural Communication

Throughout the modern age, cultural institutions created public spaces, buildings, collections and disciplines which presented mediated social narratives. These narratives were often conveyed as part of broader political, social and cultural discourses. Vested with such authority, cultural institutions came to dominate the transmission of cultural knowledge in the public sector.

This power came about in part due to relations between society and technology as they stood in the late eighteenth century. At that time, scientific culture (which was heralded as the discipline of the new age) relied on the discussion of visions in the populace through such mediums as public lectures, books and philosophical societies (Jacobs 1988, p.163-167). At the heart of these technological and social practices was the edict to transmit knowledge to the public. From the late nineteenth century onwards, museums used a variety of built and technological mediums to deliver this cultural knowledge. Museum exhibitions were used as a communicative form to transmit universal laws. Such presentations enforced the institutional position of authority over their audiences (Hooper-Greenhill 2000, p.2).

The didacticism of the early modernist museum resulted in the transmission of knowledge as patterns communicated by emerging scientific systems of representation such as evolution. Evolutionary display sought to present 'universal scientific truths' by recording and displaying species which, when collected and presented in a series, would tutor the masses in both the specific object, and the family (whether natural or cultural) from which it came. The evolutionary display method tended to reduce cultural artifacts to specimens of natural science (Bennett 1996, p.75-76).

This method of knowledge transmission was supported by technologies such as panoramas and dioramas etc. Perhaps one of the most visually arresting uses of technology at this time was Mr. Wyld's Great Model of the Globe 1851. This immersive structure included viewing galleries connected by staircases, surrounded by a ground level circular corridor housing Wyld's maps, models and plans (Black 2000, p.30). Wyld's Model of the Globe used a number of technologies to transmit knowledge about the world: whilst being analog, it shares a common theme with many of today's seemingly accessible cultural experiences - that of immersion in technology. Immersion in technology has been used extensively in "museum-like" organizations, particularly interpretative centers and theme parks.

CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS AND COMMUNICATION

Since the beginning of the modern cultural institution, community objects and stories have been collected and in the process, social relations have become cultural capital where "the politics and poetics of collecting are the politics and poetics of us all; and its messages are messages for us all" (Pearce 1995, p. 22). In that environment, the commodification of cultural content brought with it the possibility for institutions to control the value-chain of information. Possibly the most significant difference between these early symbolic conquests and the convergent new media environment is that within the modern cultural institution, collecting cultural artifacts suggested a form of "cultural violence" (Fyfe 1998, p. 330) This came about primarily due to the ways in which community information was acquired. The 'real' artifacts enabled abstract ideas to be sustained, positioning people, nations and territories and constructing boundaries to social and cultural processes. These conquests were drawn together to map out the limits of the known (Hooper-Greenhill 2000, p.18-19). In the new media environment, communities, individuals and – to a growing extent – broadcasters and institutions are working together to present cultural information. When communities and individuals have the means of production at their fingertips – such as wikis and blogs – their knowledge and access to information becomes a powerful medium through which others can consume cultural knowledge.

Beginning with the advent of broadcasting and increasing with the internet, cultural institutions have faced critical challenges which include drawing audiences into their physical spaces and providing cultural interactive experiences which are both novel and entertaining. Cultural institutions not only hold major collections, they often have state of the art resources which can be utilized to deliver their messages to a broad audience. For instance, the Singapore National Library has just re-opened on a new site with a mandate to become the premier site for the research needs of Singapore and South-East Asia (Choh 2004). The National Museum of Australia has one of the few fully functional broadcast studios in any museum world-wide and is currently utilizing these resources to stage a "Talkback Classroom International United Nations forum" which provides students from Australia and the USA with a forum to discuss issues in a broadcast recorded at the UN Headquarters in New York.

China and the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Library have recently signed with a regional bloc to promote awareness, understanding and appreciation of each others' arts and culture through artistic collaboration and exchange, joint research and study, exchange of information and people-to-people exchange and interaction. The bloc will support the conservation, protection and promotion of tangible and intangible cultural heritage through programs in cultural heritage management, protection of intellectual property rights and networking and exchange among cultural heritage agencies and organizations (People's Daily Online, 4 August 2005). Each of these examples points to a growing phenomenon whereby cultural institutions have adopted the internet as a distribution medium for their collections and public programs. Few have come to terms with the profound shift in contemporary society from 'passive' media consumption to audience interaction with content: that is, few have established distribution models which not only provide access but display and allow interaction with the products of community co-created content. The value of this content can be considered within the historical framework of cultural institutions and the ways in which they present and represent collective memory.

Institution as Cultural Broadcaster

In the late nineteenth century, memory, consciousness and time were considered to contribute to the development of a collective memory where reality was re-interpreted through a 'collection of things'. This representation became problematic when individuals lost the ability to discern that representation was derived of recollection and perception Bergson suggested that as we become conscious of an act we detach ourselves from the present and replace ourselves in the past, metaphorically and more specifically within particular sites and spaces (in Deleuze 1988, p. 222-226). This transportation from actual to "virtual" time and place enabled communities to create and recreate experiences either personal of collective. In the 1920s and 1930s, Halbwachs claimed that collective memory was rooted in concrete social experiences and associated with temporal and spatial frameworks, therefore it could be constructed by recollecting places and situating ideas or images in patterns of thought belonging to specific social groups (1992, p.78-84).

In the Victorian period, cultural institutions such as museums and libraries began to emerge as instruments of the ruling classes with a mission to educate. The communication strategies which they adopted were used to tell the story of the institution (Cassia 1992, p.28-31). In the contemporary media environment, instead of communities being defined by geographic or joint interest, the internet enables "communities of practice" which engage in a joint enterprise via mutual engagement (Wenger 1998). Agre proposes that the interactions which emerge in this mediated environment engage in some degree of collective cognition where individuals learn from others' experiences, set common strategies, develop a shared vocabulary and evolve a distinctive and shared way of thinking (1998). The local museum, library or gallery is an example of this collective cognition at work. As the communities find ways of displaying their own stories, they often draw on nostalgic memory to create 'a past' which will generate a touristic impulse (Trotter 1999, p.19-28). This collective nostalgia renders the present familiar and validates and affirms present attitudes and actions in respect to past ones (Lowenthal 1985, p.4-13). Cultural institutions have become a meeting ground for both official versions of the past and the individual or collective accounts of reflective personal experiences. Just as Wallace (1995, p.107) suggests that visitors bring a well-stocked memory of film narratives into the cultural institution, they also bring their life histories and memories.

Cultural institutions in Asia, Australia and the UK are often state-sponsored and act as custodians of cultural information. The USA operates under a different economic model where only the largest organizations are state-sponsored whilst the bulk operates in the not-for profit sector. This key economic difference affects the ways in which museums work with their communities and see their role in relation to their donors. For the purposes of this article we discuss DCC in relation to the Asian/Australian/UK model of state-sponsored institution.

DCC proposes that the cultural institution can now evolve from meeting ground to media distributor, using the life histories and personal experiences of visitors as a source of unique cultural content, thereby enabling community co-creation and providing information literacy. In contemporary media environments, cultural institutions can use new media to broaden audiences, create cultural interactive experiences and achieve broader distribution of content. The term 'new media' includes not simply interactive digital artifacts, but also new ways of consuming and producing such artifacts. Standardized internet technologies allow non-professional content creators to display and distribute new media artifacts by offering much lower 'barriers of entry' and greater immediacy than the traditional mass visual medium of television. This means that non-professional community-based creators can produce distinctive cultural content for broader audiences. Wood (2003) illustrates key points of new media in relation to broadcasting:

- New media forms should be designed around the way people live and interact with each other, rather than around the technology.

- New media provides opportunities to use the archives of media material which illustrate our past lives and cultures.

- Audiences need reliable information from trustworthy sources; therefore the context from which material is distributed is important.

- The context of audiences must be taken into account when preparing content.

Wood's summary points to the convergence of a number of resources and disciplines to explore both the narratives and experiences which result from audience engagement and interaction with content. It suggests that to create the environment for audience engagement, innovative methods will need to be developed to enable the co-creation of meaning and the generation of new content for wider audiences.

Convergent information and communication technology (ICT) has promised the delivery of multi-channel, multi-platform content where choice is in the hands of the consumer. Rabinovitch describes this as shifting consumption patterns and empowering audiences by enabling access to content on their own terms – i.e. where, when and how they choose (2003, p.74-76). Rabinovitch is careful to underpin this point with the clarification that new media has not delivered the demise of traditional media but has propelled many media companies into powerful conglomerates with stakes all along the media value chain. Convergent ICT is being used by broadcasters for the repurposing of content across multiple platforms and to facilitate greater cross-media collaboration (p.75). In terms of outcomes, the multi-channel, multi-platform challenge brings a commercial focus to the possibilities of re-purposing content for online distribution as well as describing a technology-oriented initiative to rationalize TV broadcast formats as part of digital TV developments. This initiative is consistent with the concerns of cultural institutions, particularly in the implementation of cross-platform cultural knowledge where the development of media and their impact on society have challenged both commercial and cultural organizations.

By reconfiguring relations between systems and audiences through institutions and cultural networks, new models of production, distribution and learning can be developed. Media distributors have identified a need to move beyond information archiving and display and into content generation and more porous community interface. Examining the possibilities and limitations for digital co-creation within these established, culturally rich environments will ultimately inform a model for effective low-cost digital content that will develop out of consumer-led creativity across public, community and commercial sites.

Turpeinen (2003) describes the co-evolution of broadcasted, customized and community-created media as a paradigm within which active individuals and communities use computer-mediated networking to tell and exchange their stories and to enhance the interaction among member and their peers in other groups. This form of community co-creation can both develop new paths for community knowledge and simultaneously enhance community life. Institutions which represent distributed cultural constituencies may have to work harder for audience share, and digital community co-creation programs can help the institution to the extent that such programs not only empower ground-up digital cultural creation, they also create new community audiences.

The balance of distribution between professionally produced and community co-created content is explored by Marinho (2003a, p.19) who suggests that the differing concerns of each bring its own problematic. Content distribution channels are services and tools (commodities) while social communication is the content (cultural asset) which travels along these channels and is of strategic value to both parties. When communities are engaged in the process of creating content, there is less of an opportunity for telecommunications companies to control both distribution and social communication (p. 20). Marinho's concerns stem from a belief that the convergence of media and telecommunications could create the control of the entire value chain including production of content, packaging and programming and distribution. He contends that in the process of continued and unregulated cultural convergence, cultural assets are increasingly dominated by communication companies who are often restricted in their capacity to distribute their products (2003b, p.44).

DCC seeks to circumvent this potential bottleneck in the cultural distribution process by offering cultural institutions as alternate 'channels'. For example: Australian Museums On-Line links collections across the country while the ASEAN network provides a useful example of how community knowledge can be collected and distributed across Asia. These examples provide content management systems where audiences can access cultural information from reputable sources. Institutions can promote their new partnerships by introducing communities to tools and methods for digital co-creation. The next step in the co-creation process is to ensure that community created content can be "broadcast" across the multiple platforms which the convergent new media environment allows. The next section of this paper provides examples from Australia to Thailand to highlight the opportunities that web-based cultural communication affords in relation to the creation and distribution of distinctive community created content to broader audiences.

Intellectual Property and Ownership

Issues of ownership become increasing complex when audiences partner with cultural institutions, not least because of existing restrictions on appropriate usage of content, but because institutions need to develop protocols which take into account the creative ownership of digital artifacts. Copyright laws are difficult to comprehend as categories for ownership can span multiple users. In the not-for-profit sector, this is particularly complex because museums often have different policies regarding the sale of work and leasing to commercial entities (Ellis and Mishra 2004, p.14)

Copyright serves the purpose of encouraging creativity and innovation by those who create by helping to ensure that they benefit financially from their ideas for a finite period before those ideas' utility is further exploited by their joining the unprotected 'commons'. As innovation is often a product of inspiration from existing creative works, copyright protections which are too rigid can limit creativity.

One way of approaching this is to consider restricted peer-to-peer networks as alternatives to unrestricted file-sharing. By approaching copyright in this way, the institution again provides a leadership role by encouraging their community to connect with the institutions and create content while providing mutually beneficial conditions of fair use for content. By encouraging innovation and allowing access by a wide audience, cultural institutions can again provide the infrastructure to enable the development of e-communities.

A more generalized approach to intellectual property issues has been termed the Creative Commons. Creative Commons enables copyright holders to grant some of their rights to the public while retaining others through a variety of licensing and contract schemes including dedication to the public domain or open content licensing terms (http://creativecommons.org). An excellent example of the way in which Creative Commons can be achieved within cultural institutions can be found in the development of the British Broadcasting Corporation's Creative Archive (Dean 2004). While many issues have arisen in the development of the Archive, there are some consistent problems which will be addressed throughout the development of this approach. This includes broadening the cultural debate to ensure that intellectual property decisions have a cultural dimension. Cultural identity and investment in culture are increasingly part of the creative workforce and the new economy. How we provide access to this content in democratic ways and ensure that audiences can both consume and produce creative works remain at the heart of intellectual property issues in this sector.

INFORMATION LITERACY IN AUSTRALIA

The Digital Cultural Communication method has successfully informed the authors' recent design consultancies for a number of multi-platform cultural projects in Australia, including an end-to-end community co-creation and cultural e-community program for the State Library of Queensland (Watkins and Russo 2005a), and the online expansion of a physical exhibition by the Museum of Brisbane and Brisbane Institute to connect with e-communities (Watkins and Russo 2005b).

The State Library of Queensland's Queensland Stories initiative is an end-to-end program designed to enable community members to partner with a cultural institution in the preservation and representation of cultural identity. Queensland Stories offers an opportunity for active, participating and creative individuals and communities to explore shared history through narrative, photography, audio and video. This growth of active content producing communities has required new and different tools to facilitate interaction among communities. The State Library of Queensland has provided a mobile multimedia "laboratory" which is made available for community narrative projects in regional areas of Australia. This information literacy training has powerful cultural outcomes: the community is empowered to create its own "digital stories", short multimedia narratives constructed from personal photographs and memories.

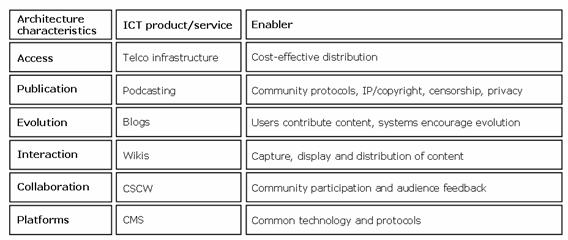

The Queensland Stories website provides a streaming media display platform for the multimedia narratives produced within the information literacies workshops. The design approach has considered the current library systems which require new audience literacies to enable consumption and production of content. By defining the characteristics of particular existing systems, information literacy architecture demonstrates how communities and institutions can describe the value of particular ICT products in the development of audience-focused outcomes. The information literacy architecture (table 1) illustrates how new media technologies can be used to enable cost-effective content creation and distribution.

Table 1: An information literacy architecture

Table 1 demonstrates some of the relationships between the types of programs or themes which the institution can proactively develop (architecture characteristics) and matches these to the types of ICT products and services which enable information literacy. The enablers illustrate the types of outcomes which can be achieved by linking institutional themes with ICT products towards common creative ends. It also seeks to define the types of information literacy which would be required to support these outcomes.

Many challenges remain within the Queensland Stories project, primarily a scarcity of workshop facilitators with the necessary information literacy to transfer skills in narrative and new media to the community. Furthermore, the limited telecommunications infrastructure within the vast yet sparsely populated state of Queensland limits many regional and remote communities to low-band dial-up internet access which prevents a satisfactory online audience experience of the digital story collection. These issues remain the focus of ongoing research and consultancy by the authors.

BLOGGING IN SOUTH KOREA

The commercial environment continues to spawn a myriad of sprawling e-communities. A particularly successful example is South Korea's "Cyworld", a personal diary-style website which features commentary, pictures and links to other sites (www.cyworld.com). Cyworld is an advanced blogging site which interconnects personal homepages, encouraging users to form a network with friends or colleagues. This network is now an e-society with 13 million residents and visitors - more than a quarter of South Korea's population. There is certainly nothing new about personal home page product – for example, the Yahoo! search engine has been offering portal personalization for years. But Cyworld could be of interest to the cultural institution wishing to extend the quality of its online experience to audiences because the concept combines interactivity, personal creativity and audience reach. In this regard, Cyworld provides a number of lessons from the commercial sector which may be of use to the cultural e-community. Firstly, the site targets a specific audience segment – the information literate twenty-something market. Cyworld has been enormously successful at drawing together a huge proportion of the South Korean youth market towards the creation, support and maintenance of a viable and highly creative e-community.

Secondly, Cyworld provides an appropriate technical infrastructure for the audience segment. Its developers have constructed an online space where audiences can create their own content, browse other user's blogs and link to relevant external pages. Cyworld is extending its services into Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore and in order to accomplish greater interaction and wider distribution, the developers are currently assessing how local relevance can be realized in each country. By providing an infrastructure specific to the needs of a particular community, Cyworld will graft diverse cultural identities to their sites to produce a localized product for each new country of distribution. This strategic approach demonstrates the proactive role that an organization can take in the development and representation of cultural identity. Importantly, it demonstrates how cultural institutions could reconsider their resources to support diverse cultural e-communities.

The third lesson from Cyworld is the use of interaction design which encourages the e-community to co-create personal content. Cyworld features its own currency, slang and particular social pressures. Cyworld community members inhabit an address or a "minihompy" (or mini-homepage). The minihompy is represented by an empty virtual room which the inhabitant then "decorates" to construct a distinctive online personality (Cameron 2005). Unlike e-communities which use blogs to further political, social or historic causes, Cyworld audiences use this site to publish their own creative efforts and to explore the possibilities of community co-creation. In so doing, Cyworld as a whole creates new media artifacts and new types of interaction which in turn strengthen the organizational impetus to support and maintain the community.

CULTURAL PORTALS IN THAILAND

While blogs and wikis provide up-to-date non-professional media for individuals to create content, Content Management Systems offer opportunities for decentralized and community-oriented modes of publishing whereby media organizations and cultural institutions evolve from gatekeepers to mediators between communities. Cultural institutions can facilitate this exchange by supporting the interchange of content and ideas while providing new tools for Digital Cultural Communication. Cultural institutions which position themselves as community providers are bound to benefit as they extend their audiences and opportunities for advertising and commerce. By providing infrastructure which includes training, institutions are in an enviable position; they own the content and manage the method of distribution. If they are able to creatively combine community creativity with customized services in innovative ways, they can extend their programs to meet the needs of individuals and small communities.

The relationship between institution, community and audience which underpins Digital Cultural Communication can be seen in a number of examples from smaller cultural institutions around the world. For example, the Ban Jalae Hill Life Tribe and Culture Center in Thailand provides a rare case study of a privately funded, community-run multi-platform cultural portal comprising:

- A solar-powered physical Center.

- An online museum.

- An end-to-end community co-creation program.

- A community TV initiative.

The Mirror Art Group which runs the Cultural Center is made up almost entirely from community members. It operates on the tenet that technology can help preserve and document a vanishing way of life, especially in communities which do not rely on written language. Most hill tribes have only developed a written script within recent generations and literacy remains extremely low. The Mirror Art Group captures cultural knowledge throughout the Northern Thai tribes in a number of ways: digital storytelling, folk music recordings, community interviews and documentation of traditional festivals.

For example, working with village elders, the Mirror Art Group has begun creating a video record of genealogical lines in surrounding Akha villages. By recording the elders reciting their genealogy and producing video compact discs, the Mirror Art Group are both documenting cultural heritage and attempting to revitalize traditional customs by broadcasting cultural content to the world, thus encouraging Akha youth to see themselves and their identities as valued within modern society. The cultural portal incorporates traditional music, videos, transcripts of genealogies as well as still images, stories and general interest for the mutual benefit of community members and broader audiences. Furthermore, the Center features a community TV initiative which keeps abreast of relevant local issues and provides positive media images to the hill tribe youth community, as well as addressing a lack of knowledge in the wider community about the hill tribes of modern Thailand (www.mirrorartgroup.org/web/projects).

The cultural portal www.hilltribe.org is supported by the institutional funding but is created by the community and maintains a strong link to the dispersed communities throughout the region. The Center also provides digital literacy outreach programs to community members with a diverse range of media products which are displayed at either the physical site, the online museum of the community TV broadcast. This represents an innovative approach to cultural representation in both site-specific (Center) and distributed (website) cultural content. In many ways, the Center's approach is similar to Cyworld:

- Infrastructure is provided to develop and maintain the community.

- Community co-created content is at the heart of the interaction.

- A specific audience is targeted.

Unlike a number of institutionally supported cultural portals, the online museum does not describe itself as an arts portal and is therefore not restricted to displaying higher art forms. Neither does it emulate other indigenous cultural portals, which focus on institutional or governance matters (for example, see the Avataq Cultural Institute and the American Indian Cultural Center). Therefore the Center presents itself as a viable and interesting case study for the ways in which cultural institutions can partner with communities and audiences to create meaningful cultural interactive experiences while broadening the distribution of cultural knowledge and utilizing media technologies to the mutual benefit of all partners.

CONCLUSION

The most pervasive communication technology within industrialized and developing societies remains broadcast television. Whether one considers this most powerful medium as a positive, negative or neutral factor upon social development, its position as a driving force of cultural globalization is widely acknowledged. To the extent that its economics often require the support of either state or corporation, broadcast television stands accused of being the propaganda mouthpiece of a ruling class or industrial elite. Although community television production can provide a more representative source of cultural information, in many countries the medium has yet to realize a significant role.

The examples discussed in this article suggest that web-based new media for social and cultural communication have made a more immediate impact on individuals and communities than pre-convergent communication forms.

In Thailand, the privately funded and community-operated Ban Jalae Hill Life Tribe and Culture Center is an innovative example of how new media technology can help preserve and document disappearing indigenous cultural identity. Through an end-to-end program of creation, interaction, distribution and information literacy, the Center supports community efforts to strengthen existing connections and disseminate cultural knowledge to a broader audience. In South Korea, the Cyworld blogging community provides an enormously successful example of the potential of addressing a specific audience segment and providing appropriate technical infrastructure to support community co-created content. Additionally, Cyworld demonstrates both how information literate, active e-communities can proliferate and how distributors can provide global infrastructure while supporting local content. In Australia, the Queensland Stories project records and archives the personal stories of a developing multi-cultural nation-state. Developed as an end-to-end program of creation, distribution and information literacy, Queensland Stories provides a compelling example of the ways in which cultural institutions can support community representation.

These snapshots clearly do not make up a compelling analysis of Digital Cultural Communication across South-East Asia, but they do serve to illustrate some of the potential of new media as an enabler of community co-creation. DCC examines the potential for co-creative relationships between cultural institution, community and audience in order to create innovative cultural content. As part of this examination, DCC considers the institutional strategies, community programs and distribution strategies required to achieve audience-focused co-creative outcomes and – unlike Virtual Heritage – provides tools and methods for the design of compelling cultural interactive experiences across multiple platforms (physical, web, mobile, broadcast). DCC is underpinned by the notion that media channels – whether commercial or institutional – can evolve from their roles of 'gatekeeper' to mediator of community knowledge. This discussion has explored some of the foundations for this cultural exchange and has provided significant and successful examples from the South-East Asia region to explore the value of new media in the dissemination of cultural content. It has outlined shifts in audience experience and the value which can be drawn from broader access to and distribution of cultural content.

REFERENCES

Agre, P. E. 1998, 'Designing Genres for New Media: Social, Economic and Political Contexts', in Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Communication and Community, ed. S.G. Jones, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Bolter, J.D., and Grusin, R. 2000, Remediation. Understanding New Media, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Borton, J. 2005, 'Tsunami bloggers in tribal news network', Asia Times. Available from: http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Southeast_Asia/GA05Ae02.html [14 September 2005].

Cameron, D. 2005 'Koreans cybertrip to a tailor-made world', The Age. Available from: http://www.theage.com.au/news/Technology/Cyberworld-imitateslife/2005/05/06/1115092684512.html?oneclick=true [13 September 2005].

Cassia, P.S. 1992, 'Ways of displaying', Museums Journal, vol. 92, pp. 28-31.

China, ASEAN to expand cultural cooperation (4 August 2005). [Online]. Available from: http://english1.people.com.cn/200508/04/eng20050804_200197.html [14 September 2005].

Choh, N.L. 2005, 'New National Library to open in July 2005', Getforme Singapore. Available from: http://www.getforme.com/previous2005/210405_newnationallibrarytoopeninjuly2005.htm [14 September 2005].

Dean, K. 2004, 'BBC to Open Content Floodgates', Wired News, 16 June. Available from: http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,63857,00.html?tw=wn_tophead_4 [10 November 2005].

Deleuze, G. 1988, Bergsonsim, Zone Books, New York.

Ellis, A. and Mishra, S. 2004, 'Managing the Creative Industries' Report to Getty Leadership Institute and National Arts Strategies for the Managing the Creative: Engaging New Audiences dialogue between for-profit and non-profit leaders in the arts and creative sectors, AEA Consulting. Available from: http://www.artstrategies.org/assets/ ManagingTheCreativeBackground.pdf [10 November 2005].

Forte, M. 2005, 'Ecology of the Virtual : New Scenarios of Virtual Heritage', Papers presented to the 11th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia in Ghent, Belgium, 3-7 October 2005. Available from: http://belgium.vsmm.org/pages/program_tuesday_keynotes.html#2

Flew, T. 2002, 'What's New about New Media' in New Media: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp. 9- 28.

Fyfe, G. 1998, 'On the relevance of Basil Bernstein's Theory of Codes to the Sociology of Art Museums', Journal of Material Culture, vol. 3, pp. 301-324.

Halbwachs, M. 1992, On Collective Memory, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hyun-oh, Y. 2005, 'Cyworld Storm Heads for Asian Countries', The Korea Times. Available from: times.hankooki.com/lpage/special/200502/kt2005022320383545250.htm [3 September 2005].

Lowenthal, D. 1985, The Past is a Foreign Country, Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 4-13.

Marinho, J.R. 2003a, 'Comments on Article 2 of the WSIS Broadcaster's Declaration', WEMF Final Report, World Electronic Media Forum, pp. 19-20. Available from: http://www.wemfmedia.org/documents/final_report.pdf [30 August 2005].

Marinho, J.R. 2003b, 'Keynote Address, Media Freedom in the Information Society', WEMF Final Report, World Electronic Media Forum, pp. 44-45. Available from: http://www.wemfmedia.org/documents/final_report.pdf [30 August 2005].

Mattleart, A. and Mattleart M. 1998, Theories of Communication, Sage, London.

Pearce, S. 1995 'Collecting as medium and message', in Museum, Media, Message, ed. E. Hooper-Greenhill, Routledge, London, p. 22.

Russo, A. and Watkins, J. 2005, 'Digital Cultural Communication: Audience and Remediation' in Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage eds. F. Cameron and S. Kenderdine, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press (in press).

Russo, A. and Watkins, J. 2004 'Creative new media design: achieving representative curatorial practice using a Cultural Interactive Experience Design method' in Interaction: Systems, Practice and Theory, eds. E. Edmonds and R. Gibson. ACM SIGCHI, pp.573- 597.

Trotter, R. 1999, 'Nostalgia and the Construction of an Australian Dreaming', Journal of Australian Studies, vol. Dec, pp. 19-28.

Turpeinen, M. 2003, 'Co-Evolution of Broadcasted, Customized and Community-Created Media',

in Broadcasting & Convergence: New Articulations of the Public Service Remit, eds. G. F. Lowe and T. Hujanen, Nordicom, Göteborg.

Wallace, M. 1995, 'Changing media, changing messages', in Museum, Media, Message, ed. E. Hooper-Greenhill, Routledge, London, pp. 107-123.

Watkins, J. and Russo, A. 2005a, 'Digital Cultural Communication: designing co-creative new media environments' in Creativity & Cognition, Proceedings 2005, ed. L. Candy, ACM SIGCHI, pp. 144-149.

Watkins, J. and Russo, A. 2005b, 'Extending Site-Specific Audience Experience via Multi-Platform Communication Design, in Internet and Multimedia Systems and Applications, Proceedings, ed. M.H. Hamza, Calgary, ACTA Press.

Wenger, E. 1998, Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Wood, D. 2003, 'New Media: Time Machine for the 21st Century', WEMF Final Report, World Electronic Media Forum, pp. 74-76. Available from: http://www.wemfmedia.org/documents/final_report.pdf [1 September 2005].

Web references

Avataq Cultural Institute - http://www.avataq.qc.ca/

Creative Commons - http://www.creativecommons.org

Cyworld - http://cyworld.com

American Indian Cultural Center - http://www.nacea.com

National Museum of Australia - http://www.nma.gov.au

Queensland Stories, State Library of Queensland - http://www.qldstories.slq.gov.au

Singapore National Library - http://www.nlb.gov.sg/CPMS.portal

Virtual Hilltribe Museum - http://www.hilltribes.org

Ban Jalae Hilltribe Life and Culture Center –

http://www.hilltribe.org/museum/01-museum-banjalae.html

Mirror Art Group - http://www.mirrorartgroup.org/web/projects/

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=107&layout=html

|