Where S A = Strongly Agreed (5); A = Agreed (4); U = undecided (3) ; D = Disagree (2); S.D = Strongly disagreed = 1; M= men’s view; W= women’s view. Total number (∑F ) = 50 each for both men and women; mean score = ∑ rating point × observation / ∑F

Table 2: Poverty level of Nigerian (1980-1996)

Source: FOS poverty profile for Nigeria: 1980 – 1996 in draft national policy on poverty eradication (2000)

Table 3: Incidence of poverty in Nigeria 1985-92 (%)

Source: Canagarajah, S. et. al (1997)

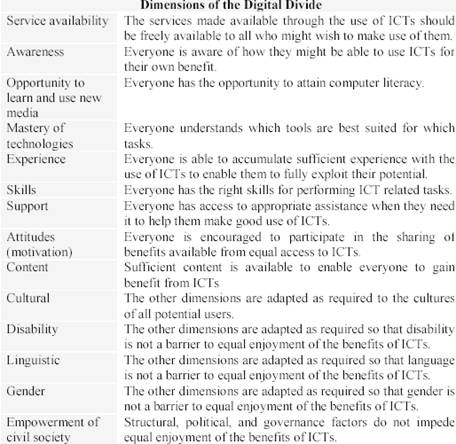

Table 4: Dimensions of the Digital Divide

Source: Roger Harris (2002): ICT for Poverty Alleviation Framework Table 5: Nigeria Poverty profile, 1980-1996

Source: FOS (1999): Nigeria Poverty profile, 1980-1996

Table 6: Poverty incidence and crop mix, 1996 (%)

Source: FOS (1999): Poverty incidence and crop mix, 1996

Table 5 showed that poverty is a serious threat among the farming population in the rural areas of Nigeria. The level of poverty in the farming population was consistently higher than that of the non-farming population and it was also higher in the rural than the urban areas. Further analysis from the table shows that households headed by farmers consistently experienced the highest level of poverty (compared to the other occupation groups and the national average) in each of the years, except 1996 when the level of poverty was marginally lower (71.0 percent) than that of the service sector (71.4 percent). A large proportion (25 percent) of farmers specializing in food production were above the poverty level compared to the farmers growing export crops only (22.7 percent); although both groups suffered a similar level of extreme poverty. It may be inferred that the food growers would be more food secure, given their access to the own-consumption; whereas the export crop growers could be less food- secure, since they have to depend on market purchases. Farmers who produced both food and export crops did not much better; as much as 31 percent of them were above the poverty line, and the proportion of their group which suffered extreme poverty (35 percent) was about ten percent lower than the similar proportion of farmers who specialized in either food or export crop production. Table 7: Anti – Poverty Programmes by the Government of Nigeria, 1986 to date

Source: (i) Oladeji and Abiola, (1998); (ii) CBN (2003): Annual report and statement of Accounts Following the above trend, a great number of efforts have been initiated by the Nigerian government and the international communities have been at improving basic services, infrastructure and housing facilities for the rural and urban population as well as extending access to credit and farm inputs, and creation of employment (see Table 7) but they have not succeeded in changing the living situation of the very poor people. This was found from the study to be as a result of inconsistency and non-implementation of government policies to the letter. Most of the programs seemed to have benefited those who were less needy and already on their own feet economically. The phenomenon which can best be termed as 'the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. Those living in poverty are often denied access to critical resources such as credit, land and inheritance.

Table 8: Programme of the National Directorate of employment

Source: Computer by the Authors in 2005 from CBN annual reports and statement of account (various issues).

(c) The roles of gender and their levels of involvement poverty in Nigeria In the past decade the number of women living in poverty has increased disproportionately to the number of men, particularly in the developing countries, even though the proportion of women begging for arms in the streets is less than those of men. In addition to economic factors, the rigidity of socially ascribed gender roles and women's limited access to power, education, training and productive resources are also responsible. Many experience a life that is a complex web of multi-roles and multi-tasks, which requires the average woman to conduct 'different roles at different times in a bid to fulfill her family’s needs’. The role of women in Nigerian society is changing, but not always to their advantage. They generally work much longer hours than men do. They provide an estimated 60–80 per cent of the labour in agriculture through the production, processing, and marketing of food. They assist on family farms and are farmers in their own right. They are responsible for fetching water and fuel wood and act as 'the most important health worker for their children. So, Nigerian women are in an important position to contribute to food security, nutrition, and the overall health status of the family. But they are inadequately recognized or rewarded for their efforts at any level. They are affected by poverty in different ways, depending upon their age, race, ethnicity, linguistic background, ability, sexual orientation, and citizenship. They constitute more than half of the world’s population and more than 70 per cent of the world’s poor. Given the harsh realities of increasing poverty in the country, Nigerian women experience poverty in the following ways: economically through deprivation; politically through marginalization in terms of their the denial of the rights to land ownership (inheritance) and access to credit facilities and other inputs; socially through discrimination in terms of their participation in decision-making at home and in the community; culturally through ruthlessness; and ecologically through vulnerability. They receive less than 10 per cent of the earnings or credit available to small farmers. Although there is a scarcity of documentation about women’s role in relation to land ownership and farming in Nigeria, but statistics on land registration show that 90 per cent of all land in the country is registered in men’s names. Nigerian women have always worked on farms, yet have never been allowed to own any land. Findings from UNIFEM (2000) have revealed that in the formal sector, women constitute 30 per cent of professional posts, 17 per cent of administrative/managerial positions, and 30 per cent of clerical positions; 17 per cent are employed in 'other’ categories. Women are disproportionately concentrated in low-paid jobs, particularly in agriculture and the informal sector. The Federal Office of Statistics has noted that 48 per cent of women are engaged in agricultural work, and 38 per cent are involved in petty trading at markets, although it is common knowledge that most rural women conduct both roles. Women and young girls in Nigeria are burdened with an unfair workload inside and outside the home. Data suggest that 33 per cent of women work five or more days per week for very long hours to supplement the family income. In rural areas, aside from their reproductive and housekeeping roles, women must fetch water and firewood, in addition to conducting much of the agricultural work in the fields such as planting, hoeing and weeding, harvesting, and transporting and storage of crops. Research has revealed that 41 per cent of working mothers have to attend to their children while at work. Women in urban areas have little support from their extended family or community and so are forced to take their young children with them to work. Or the infants are left with older female siblings while their mothers are at work, which prevents the older girls from attending school, and partly explains the high levels of illiteracy among young girls. Men in Nigeria have much greater control over resources than women do. As a result of this, Nigerian government has initiated series of programmes to assist women in obtaining micro-finance and credit, formation of co-operatives and self-help organizations such as Federation of Nigerian Women’s Societies (FNWS) in 1953, formation of National Women’s Commission was set up (later upgraded to the Ministry for Women’s Affairs and Social Development), Family Support Programme (FSP) and Family Economic Advancement Programme (FEAP). However these programmes have not achieved the desired goal as the situation has not changed. The macro-economic reforms under the Structural Adjustment Programmes and the prevalence of human-rights abuses, cultural barriers and the high level of illiteracy among females are some of the factors that have further plunged women into deeper poverty in Nigeria. Continued denial of gender’s rights and lack of recognition of their important role in the agricultural labour force is another factor that further compound Nigerian women poverty level a phenomenon that can be termed as 'feminisation’ of poverty. Recent result of a joint research by the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN), in a joint venture with UNICEF (2002) has shown that women and children in Nigeria are among the poorest in sub-Saharan Africa and the developing world. In response to UN initiatives, Nigeria recently formulated a National Policy on Women. The policy is an attempt to incorporate women fully into national development as 'equal partners, decision-makers and beneficiaries’ of Nigeria, through the removal of gender-based inequalities. The policy aspires to the inclusion of women in all spheres of national life, including education, science and technology, health care, employment, agriculture, industry, environment, legal justice, social services, and the media. It aspires to eliminate the negative aspects of Nigerian culture, which serve only to harm women, and it aspires to challenge the patriarchal status quo. (d) Uses of ICT for gender empowerment in Nigeria Recently, information is observed, as a prerequisite for empowerment9 (World Bank, 2002) and participation drives empowerment by encouraging people to be active in the development process, to contribute ideas, take initiative, articulate needs and problems and assert their autonomy (Ascroft and Masilela, 1994). ICT is the latest in the series of continuing technological revolutions, and is argued to have significant influence on gender empowerment (van Ark et al, 2002). Informed citizens according to World Bank report (2002) are better equipped to take advantage of opportunity, access services, exercise their rights, and hold state and non- state actors accountable. Social influences on women's relationship to technology affect their attitudes toward ICTs. The tendency to direct women into non-technological professions and responsibilities means that women feel "fear and embarrassment" when dealing with ICTs. A study in Nigeria revealed that women considered the word "technology" to have male connotations, even though "information" seemed more feminine. Some even believed that working with ICTs would drive women mad. These examples indicate a high level of discomfort with new information technologies. There is therefore the need for greater concentration on the use of ICT for gender empowerment in Nigeria. For instance, United Nations Millennium Declaration (2005) has resolved to ensure that globalization becomes a positive force for all the world's people and to promote gender equality and empowerment of women as effective ways to combat poverty, hunger and disease and to stimulate development that is truly sustainable, and to ensure that the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications technologies, are available to all. Women’s full and equal access to ICT-based economic and educational activities supports women's contributions in both business and home-based activities and improves women's socioeconomic status, strengthens the family, and provides access to information, communication, freedom of expression, and formal and informal associations. ICTs also provide options for women, including overcoming illiteracy, creating opportunities for entrepreneurship, allowing women to work from home and care for their families, accessing ICTs from rural locations, and enhancing and enriching their quality of life. (e) Uses of ICTs in the enhancement of economic livelihood of the poor in Nigeria ICTs are often viewed as near-magic solutions to problems. They are extremely powerful tools that have proven useful in many areas of Nigeria. Traditional media and new ICTs have played a major role in diffusing information to poor living in rural communities. Although little empirical evidences of the benefits of ICTs in Nigeria are found in literatures, there are great potentials of ICTs as tools for enhancing peoples daily lives whether by increasing access to information relevant to their economic livelihood, better access to other information sources; healthcare, transport, distance learning or in the strengthening of kinship. The result from this study showed that, the most common of the ICTs related to poverty alleviation programs in Nigeria are telephone and radio. While other commonly uses of traditional media include: Print, video, television, films, slides, pictures, drama, dance, folklore, group discussions, meetings, exhibitions and demonstrations (Munyua, 2000). The use of computers or the Internet is still restricted to very few people living in urban centres. ICTs have the potential to broaden and enhance access to information and communication resources for remote rural areas and poor communities, to strengthen the process of democratization and to ameliorate the endemic problem of poverty (Norrish, 2000). With the privatization of the Nigeria Telecommunication system, mobile phones are increasingly becoming affordable by average Nigerian (the poor), and they help to overcome rural isolation and make communication easier. The wireless technologies have entered remote rural areas thereby reducing the reliance on costly fixed telephone infrastructures. In many rural areas, over 50% of households make regular use of the telephone when compare with few years ago when the figure was less than 5%. Such accessible communications are now been used for family contact, reduction of the necessity for trips, access to government services, and much more. Both radio and telephone are now operating in Nigeria regardless of the language spoken and do not require literacy, which helps in explaining the exceedingly high utility and utilization of both. The Internet-based communications is however found to remain the least effective in majority of the rural areas of Nigeria because the resource thresholds are far higher, typically requiring higher-quality communications, electricity, technology infrastructure, and literacy in a computer-supported language. ICTs are also found as tools that open new opportunities and new threats (often by virtue of each other). They have a far more enabling role in building the capacity of the intermediary institutions that work for poverty, rather than directly affecting poor themselves. ICTs have the greatest potential to act as a facilitator for specific development initiatives such as the cassava, rice initiative programmes that are currently operational at grass roots in Nigeria. Access to ICTs provides information on prices, markets, technology, and weather to the poor farmers. Community-based telecentres have the potential to empower rural communities and facilitate socio-economic developments in agriculture. It uses selected ICTs (e-mail, Internet, phone, radio, TV, print) to accelerate the wider delivery of appropriately packaged agricultural information and other relevant information useful for the poor. ICTs offer information and knowledge, which are critical components of poverty alleviation strategies; they make available easy access to huge amounts of information useful for the poor. Through the new technology, particularly networked Internet technologies, anyone can find almost anything. There are fewer secrets, and fewer places to hide. Educated but poor farmers and traders in Nigeria are now promoting their products and handle simple transactions such as orders over the web with payment transactions for goods being handled off-line (O’Farrell et al 1999). Evidence has also shown that eventhough trading online is not a common practice by the poor Nigerian; the technology is cheaper and faster paper-based medium, telephone or fax. Electronic-commerce enables entrepreneurs to access global market information and open up new regional and global markets that fetch better prices and increase earnings. The lack of adequate healthcare is one of the most onerous aspects of poverty. There has been significant focus on using ICTs to actually deliver healthcare (telemedicine) and as a way of educating people on health issues in Nigeria. For instance, preventive measures of AIDS and current incident of bird flu are communicated to the poor through television, Internet, radio, posters etc. However, there are other uses of technology, which have the potential for revolutionary improvements in the delivery of healthcare. In most cases, the technology is being used in its simplest forms to aid in the collection, storing and retrieval of data and information. ICTs have assisted Nigeria in the reduction of unemployment rates at national, urban and in rural areas of Nigeria. Through the establishment of rural information centers in most parts of the country, ICTs have created employment opportunities in rural areas by engaging telecentre managers, subject matter specialists, information managers, translators and information technology technicians. Such centers have helped to bridge the gap between urban and rural communities and reduce the rural-urban migration problem. The centers have also provided training and those trained have now become small-scale entrepreneurs in their respective areas. Thousands of the poor Nigerian has also benefited from telephone service through sales of either accessories or Telephone calls (make calls, receive calls). Sound decision-making is dependent upon availability of comprehensive, timely and up-to-date information. Food security problems facing Nigeria demonstrate the need for informed researchers, planners, policy makers, development workers and farmers. Information is also needed to facilitate the development and implementation of food security policies. Introduction of mobile phone in Nigeria has helped in transmitting information to and from rural inaccessible areas. ICTs have helped in the empowerment of a number of rural communities in Nigeria and give them "a voice"10 that permits them to contribute to the development process. With ICTs, many rural communities acquire the capacity to improve their living conditions and become motivated through training and dialogue with others to a level where they make decisions for their own development (Balit 1998). According to the ILO (2001), ICTs have assisted significantly in socio-economic development of many poor Nigerian. In Nigeria, the ICTs have also helped to impact on the livelihood strategies of small-scale enterprises and local entrepreneurs as well as in the enhancement of various forms of social capital11. A proportion of the research literature discusses social capital and ICT from general internet studies as well as specifically place based research (O'Neil 2002). Social capital theory, particularly since Putnam (2000), has attracted the attention of scholars working to understand ICT in local as well as historical communities. While Putnam’s theory focuses on the value of bridging across-group social ties, earlier social capital theory particularly Coleman (1988), emphasizes the value of bonding within-group social ties. ICTs initiative is part of existing social interactions, they reduce the friction of space not the importance of place (Hampton 2004). The technologies have been viewed as part of a complex ecology of communication tools that enable local social interactivity. For instance, the Internet is a tool for maintaining social relations, information exchange, and increasing face-to-face interaction, all of which help to build both bonding and bridging social capital in communities (Kavanaugh and Patterson 2001). ICT initiatives play a significant role in developing and sustaining local social ties and stronger ties are characterized by broader media usage (Haythornthwaite,2005). The use of ICTs in the enhancement of various forms of Household livelihood assets including social capitals following de satge et al (2002) are highlighted as:

Through the use of ICT, some information on effects of environmental degradation that causes poverty is communicated through radio. The radio plays are communicated in several local languages to people. These have helped many communities to improve their conservation practices. New ICTs12 though not commonly used by majority in Nigeria as compared with the old ICTs13 and really old ICTs14 have the potential to penetrate under-serviced areas and enhance education through distance learning. The new ICTs facilitate development of relevant local content and faster delivery of information on technical assistance and basic human needs such as food, agriculture, health and water. Farmers can also interact with other farmers, their families, neighbors, suppliers, customers and intermediaries and this is a way of educating rural communities. The Internet can also enable the remotest village to access regular and reliable information from a global library (the web). Different media combinations are used in different cases through radio, television, videocassettes, audiocassettes, video conferencing, computer programmes, print and CD-ROM or the Internet (Truelove 1998). Rural areas also get greater visibility by having the opportunity to disseminate information about their community to the whole world. (f) Constraints of linkages between ICTs and poverty reduction in Nigeria In examining the linkages between ICTs and poverty reduction; few scholars have paid close attention to the constraints that exist for poor to harness the potential benefits of ICTs. The key constraints facing ICTs in poverty alleviation in Nigeria are: lack of access to electricity / unstable supply of electricity and the lack of adequate technical support. These constraints according to Heeks (1999), Melkote and Steeves (2001) referred to as "technological constraints". Electricity is basic to Internet access and ICT use. The result from the survey showed that over 75% of rural Nigeria are still in the dark without power for lighting, let alone for running computers or TVs. Other constraints also observed from the study include: evaluating information, constraints in applying/using Information. Available evidence strongly suggests that such constraints are driven by socio-economic development, so that access to ICT diffusion reflects and reinforces traditional inequalities between the rich and the poor communities (Norrish, 2000). The poor and socially excluded are unlikely to "reap the benefits" of ICTs due to deep divisions of social stratification such as patterns of household income, education, occupational status disempowerment etc. (g) Connections between ICT and anti- poverty measures in Nigeria ICTs have been used as an integral part within the framework of the government policy plans on poverty alleviations programmes in Nigeria even while the same contextual problems such as corruption, marginalization of women in credit earning that caused the earlier movements to fail still exist. Most government poverty alleviation programmes through ICT (such as radio, newspaper, mobile phone etc) are now been communicated to the very poor the programmes are meant for. Monitoring of poverty alleviation programmes, feedback from the beneficiaries /non-beneficiaries is now been done through ICTs such as "radio weekly link programme" Presidential monthly chart" etc. At the national, States and local level in Nigeria people can express their views on the performance of government anti- poverty programmes chatting with the president, governors or the local government chairperson as well as officers directly in charge of the execution of such programmes. In addition, anti-poverty measures introduced through the use of ICT has been able to generate substantial amount of employment through the use of mobile phone by many Nigerian to sustain a living. There are many call centers in villages and towns mostly operated by people between age distributions of between 20-29 years (38%), mostly women with secondary/ post secondary education in Nigeria. Some of these people run shops for the sale of Global System of Mobile (GSM) accessories as a major form of occupation as means of self-employment as well as a means of sustaining livelihood (80% and 84% respectively as shown in Table 9). Past studies have shown that over 2,000 persons are directly employed by GSM operators and an estimated of 40,000 Nigerians are benefiting from indirect employment generated by GSM operators in Nigeria (Ndukwe, 2003). ICTs have also assisted in the area of micro-credits finance and cooperatives. Farmers are now organizing cooperatively to manage their access to market as an alternative to being at the mercy of powerful buyers. Credits are now easily made available to the poor for a better quality of life through such social groups and ICTs.

Table 9: Distribution of respondents according to their demographic characteristics and ownership/ operators of mobile phone call centre

Note: reasons for owning call centre are a multiple response; Source: field survey, 2006

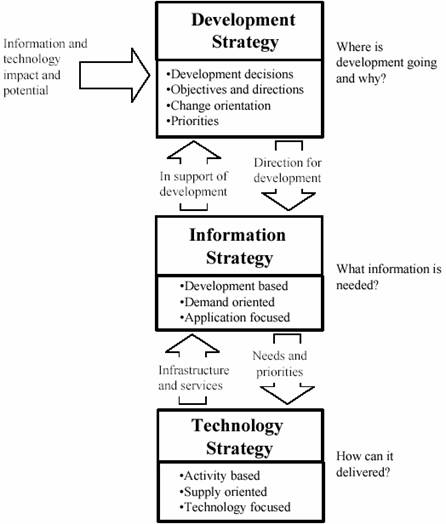

Through the use of ICTs such as the GSM telephone, transaction costs of many Nigerian who are poor have drastically been reduced. People make called before traveling and for business transaction. The technology has led to increase service innovation, efficiency and productivity. (h) Steps Nigeria can take to explore full potential of ICT in Poverty Alleviation Focussing on the use of ICT alone does not lead is not the only means of gender empowerment and sustainable poverty alleviation in Nigeria. However, the most effective route to achieving substantial benefit with ICTs is to concentrate on re-thinking development activities by analysing current problems and associated contextual conditions, and considering ICT as just one ingredient of the solution (see figure 1). Application of ICTs for poverty should always begin with a development strategy. From that, an information plan can be derived and only out of that should come a technology plan. In doing this bottom-up, demand-driven should be followed; gender and the poor to be empowered must be allowed to appreciate the needs while they must be alleviated by allowing them to express their developmental needs, That is, they should be allowed to construct their own agenda for ICT-assisted development, prior to introducing the technology.

Figure 1: Relationship between development, information and ICTs

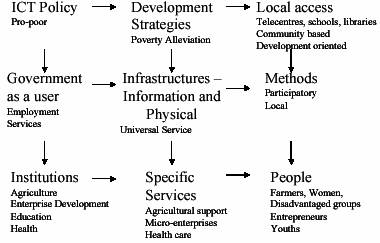

As part of pro-poor ICT policy in Nigeria, government must acknowledge its role as a major employer and user of ICTs. This must begins with a development commitment that targets poverty alleviation. This will fosters the infrastructure development that will be required to achieve widespread poverty alleviation through local access combines with suitable methods to ensure access is used to the best effect. There is the need for the Nigerian government to encourage institution reform leading to the delivery of effective services capable of exploiting the infrastructure. The services must be directed towards and delivered to the local access points to the poor people who need them (see figure 2).

Figure 2: A framework for poverty alleviation with ICTs

Government should also realise that eliminating the problems that the digital divide15 represents requires more than the provision of access to technologies. According to the ILO, ICTs can contribute significantly to socio-economic development, but investments in them alone are not sufficient for development to occur (ILO, 2001). That means that telecommunications is a necessary but insufficient condition for economic development. Application of ICT is a necessary but not sufficient resource to address problems of the poor that mostly reside in the rural areas of Nigeria without adherence to principles of integrated rural development .So, unless there is minimal infrastructure development in transport, education, health, and social and cultural facilities, it is unlikely that investments from ICTs alone will enable rural poor in Nigeria to cross the threshold from decline to growth. The digital divide then goes beyond access to the technology and can be expressed in terms of multiple dimensions. If Nigeria wishes to share the benefitsof access to technology, further provisions have to be implemented in order to address all the dimensions of the digital divide. These include a variety of societal concerns to do with education and capacity building, social equity, including gender equity, and the appropriateness of technology and information to its socio-economic context. The poor people must understand digital divide and they must be thought to use and have access to ICTs (see table 4).

RECOMMENDATIONS In order for Nigeria to be economically competitive, politically stable, and socially secure, there is the need to utilize technology in making advances in health, politics, education, business, agriculture, consumer goods, national security and poverty reduction. The country needs to focus its attention on the development, access, and implementation of ICTs both in the rural area where majority of the poor resides and in the urban centers. Formation of women association, farmer associations and Community-bases organisations at rural areas will act as training centres and access points for ICTs. From such group, the poor will be thought on how to use computers for word processing, making complex calculations and tables of their work plans and income and expenditure. The access points will also play the role of information centres where price lists, weather forecasts will be available in any form either as print, digital, audio, video form. To achieve these, the following are further recommended

CONCLUSIONS This paper revealed a deeply troubling social phenomenon in Nigerian society: increasing widespread poverty and failed attempts to create sustainable policies to address this problem. The programmes are not sustainable because the key stakeholders, the 'poor’ whose feelings and actions constitute the major success factor for the programmes are often not aware or consulted. Sustainable poverty reduction will therefore require not only the proper identification of the poor (including their characteristics and survival strategies), but the use of ICTs which offer unprecedented opportunity for decentralizing information access and creation. A narrow ICTs view is just as futile as a narrow feminist view. Poverty problem being multidimensional therefore requires politically conscious social organization. ICTs become essential tools in alleviating poverty through the enhancement of social capital and economic of livelihood of the poor in that, it helps to remove information distortion which often makes it difficult to monitor the rate of cheating of eligible families excluded from poverty alleviation programme in the past. Involvement of gender in the formulation of poverty reduction programmes will help in achieving the desire results since they can spend all there resources for the survival of members of their family as well as been good resource managers. ICTs also help in stretching implementation energies to the full. The new ICTs have the potential of getting vast amounts of information to rural populations in a more timely, comprehensive and cost-effective manner, and could be used together with traditional media.

Endnotes (click on the number to return to that point in the text) 1 This is not to say that there is no definition of poverty. There are many, with different groups each using their own version. 2 Job that meets the needs for the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs 3 ICTs refer to any electronic means of capturing, processing, storing and disseminating information. ICT is a combination of information technology (IT) and communication technology (CT). The former involves the processing and packaging of information, while the latter is concerned with the interaction, exchange and linkage with information and data bases between users via networking. The coverage of ICT goes beyond such activities as programming, networking and analyzing. It enables the usage of computers and related tools to enhance the quality of products, labour productivity, international competitiveness and quality of life. 4 To alleviate Poverty means the process of freeing the poor from their state of poverty, the process of empowering the poor to get out of their poverty state. 5 Poor people are those that have been denied of choices and opportunities for living a tolerable life (United Nations, 1997). 6 Gender is the socially constructed relations between women and men in a particular society but in the content of this study refers to women 7 "Scheme" as used in the study implies "job" 8 "School leaver" refers to those that have finished secondary school but without any job 9 Empowerment: This is the expansion of assets and capabilities of poor people to participate in, negotiate with, influence, control and hold accountable the institutions that affect their lives 10 Giving rural people a voice means giving them a seat at the table to express their views and opinions and become part of the decision making process. 11 Social capital has been defined as the capacity of groups to work together for the common good (Montgomery, 1998) or as the ability to draw on relationships with others especially on the basis of trust and reciprocity (HDR, 1998 12 New ICTs: Computers, satellites, wireless one-on-one communications (including mobile phones), the Internet, e-mail and multimedia generally fall into the New ICT category. The concepts behind these technologies are not particularly new, but the common and inexpensive use of them is what makes them new. Most of these, and virtually all new versions of them, are based on digital communications. 13 Old ICTs: Radio, television, land-line telephones and telegraph fall into the Old ICTcategory. They have been in reasonably common use throughout much of the world formany decades. Traditionally, these technologies have used analog transmission techniques,although they too are migrating to the now less expensive digital form 14 Really Old ICTs: Newspapers, books and libraries fall into this category. They have been in common use for several hundred years 15 Something that seems to require mere technology to redress socio-economic inequalities

REFERENCES Anderson, Jon (1999). Applying the lessons of participatory communication and training to rural telecentres. FAO, Rome Italy. At: http://www.fao.org/sd/Cddirect/Cdan0017.htm Ascroft, J. and S. Masilela (1994). "Participatory Decision-Making in Third World Development". In White, S. A., Nair, K. S. and Ascroft, J. (eds.) Participatory Communication. Working for Change and Development. New Delhi, Sage Publications. Arunachalam, S., (2002). "Reaching the Unreached: How can we use ICTs to empower the rural poor in the developing world through enhanced access to relevant information?" 68th IFLA Council and General Conference, Glasgow, August 18-24, 2002 Awe B. (1997). "Evaluation of selected women economic adjustment programmes". In Garga P. K. et al (ed). Women and economic reforms in Nigeria. Ibadan: WORDOC IAS, University of Ibadan Balit, S. in collaboration with FAO Communication for development Group (1999). Voices for change: rural women and communication. FAO Extension and Training Division. Communication for Development Group, Extension Education and Communication Service.pp37 Balit, S. (1998). Listening to farmers: communication for participation and change in Latin America. In Training for agriculture and rural development: 1997-98. FAO, Rome Italy. pp. 29-40. At: http://www.fao.org/sd/Cddirect/Cdan0018.htm Canagarajah, S., J. et.al. (1997). "Evolution of Poverty and Welfare in Nigeria: 1985 – 92", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 1715. CBN (1960- ). Central Bank of Nigeria Annual Report and Statement of Accounts (various issues). CBN (1997). Central Bank of Nigeria Annual Report and statement of Account. CBN (1998). Central Bank of Nigeria Statistical Bulletin. CBN (1998, 2003). Central Bank of Nigeria Annual Report and statement of Accounts. CBN (2000). The Changing structure of the Nigerian Economy and Implications for Development, Lagos: Realm Communication / Central Bank of Nigeria. Coleman, James S.(1988). "Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital." American Journal of Sociology 94, no. Supplement: Organizations and Institutions: Sociological and Economic Approaches to the Analysis of Social Structure : S95-S120. Colle, R. (2000). Communication Shops and Telecentres in developing Countries, in Gurstein, M. (ed.) Community Informatics: Enabling Communities with Information and Communications Technologies, Idea Group Publishing, Hershey, USA. Cornelissen A. M. G (2003). The two faces of sustainability: Fuzzy evaluation of sustainable Development, University of Washington, Wageninigen. Deepa N; R Patel; K. Schafft; A. Rademacher and S Kock-schulte (2000). Voices of the Poor. Can anyone hear us? Published by Oxford University press for World Bank de Satge, R Hollway, A Mullins, D Nchabaleng, L and Ward, P (2002). Learning about livelihoods. Insights from Southern Africa. Peri peri and Oxfam Egware, L (1997) "Poverty and Poverty Alleviation: Nigeria’s Experience". In Poverty Alleviation in Nigeria, Selected Papers for the 1997 Annual Conference of Nigerian Economic Society. FGN (2000). Draft National Policy on Poverty Eradication. ABUJA: federal Government of Nigeria. FGN (2001). National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP). ABUJA: Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). Federal Office of Statistics (1999) Poverty Profile for Nigeria: 1980 – 1996. Garson, D. (ed.), (2000). Social Dimensions of Information Technology: issues for the new millennium. London: IGP. Gopalakrishnan, T. R (2005). "Exploring Old Terrains with New Technologies: Making ICT Services and Applications Work for the Poor". Paper presented at IFIP WG 9.2 Conference on Landscapes of ICT and Social Accountability held on June 27-29, 2005 at University of Turku, Turku, Finland. Hampton, K. (2004). "Neighbourhoods and new technologies: connecting in the Network Society". Neighborhoods and New Technologies, London, The Work Foundation. Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). "Social networks and internet connectivity effects". Information, Communication and Society 8(2): 125-147. Heeks, R. (1999). Information and communication technologies, poverty and development. Development Informatics Working Paper Series. Paper no. 5. Institute for Development Policy and Management, Manchester (UK). 19 pp. ILO (2001). ILO/Japan Tripartite Regional Meeting on Youth Employment in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok, 27 February, to March 1. Kavanaugh, A. and S. J. Patterson, (2001). "The impact of community computer networks on social capital and community involvement." American Behavioral Scientist 45(3): 496-509. Mansell, R., and I. Schenk (1998). Net Compatible: Virtual Communities, Intelligent Agents and Trust Service Provision for Electronic Commerce. Brighton: SPRU, p. 70 Mansell, R.; Wehn, U. (eds.), 1998. Knowledge Societies: Information Technology for Sustainable Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press Melkote, S. and Steeves, H. L. (2001). Communication for Development in the Third world. Theory and Practice for Empowerment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Munyua, H. (2000). "Application of information communication technologies in the agricultural sector in Africa: a gender perspective". In Rathgeber, E. and Adera, E. O. (eds) Gender and Information Revolution in Africa, IDRC/ECA. pp. 85-123. Ndukwe E (2003). The roles of Telecommunications in National Development. Paper presented at the 19th Omolayole annual management lecture on Friday December 5 2003 at Chartered Institute of Bankers’ auditorium Victoria Island Lagos Nigeria Norrish, P. (1999). Advancing telecommunications for rural development through participatory communication. At: http://www.fao.org/sd/Cddirect/Cdan0025.htm Nwaobi, G.C. (2000). The Knowledge Economics Trends and Perspectives, Lagos: Quanterb / Goan Communications. O’Farrell, C., Norrish, P. and Scott, A. (1999). Information and communication technologies (ICTs) for sustainable livelihoods: preliminary study. April – Nov 1999. Ogwumike, F.O (2001). "Survey of approaches to poverty alleviation programmes: general perspectives". Paper presented at the NCEMA Training programme on poverty alleviation policies and strategies. 15-26 October. Oladeji, S. I. and Abiola A. G. (1998). "Poverty Alleviation with Economic Growth Strategy: Prospects and Challenges in Contemporary Nigeria". Nigerian Journal of Economic and Social Studies (NJESS), Vol. 40, N0. 1. Omonona, B. T., E J Udoh and M, I Owoicho (2000). "Urban people’s perception and causes of poverty: A case study of Agbowo community in Ibadan". Nigeria Agricultural Development Studies vol.1 No.1 pp 90-99. O'Neil, D. (2002). "Assessing community informatics: a review of methodological approaches for evaluating community networks and community technology centres." 12(1): 76 -102. Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000. Roger Harris (2002). ICT and Poverty Alleviation framework: prepared for the UNDP workshop for UNDP countries office ICP programme officers/ focal points in Asian Specific. Roger Harris Associates. Hong Kong Rommes, E., (2002). Gender Scripts and the Internet. Philosophy and Social Sciences. Enschede: Twente University, p. 300 Sen, A. (1999). Hunger and Public Action, Oxford: Clarerdon Sharpe, M., (2000). IST 2000: Realising an Information Society for all. Brussels: European Commission, p. 150 Spears, R.; and T. Postmes, T. ( 2000). Social Psychological Influence of ICT's on Society and their Policy Implications. Amsterdam: Infodrome, p. 80 Truelove, W. (1998). The selection of media for distance education in agriculture. At: http://www.fao.org/sd/Cddirect/Cdan0017.htm United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) (2000). Progress of the World’s Women 2000. United Nations: New York. http://www.unifem.undp.org/progressww/. [Accessed 11 August 2002. United Nations (2005). The Millenium Development Goals Report 2005; Valenduc, G and Patricia Vendramin (2005). Work organisation and skills in ICT professions: The gender dimension. ICT conference on the Knowledge, Society and Changes in Work. Den Haag, 9-10 June 2005 World Bank (1996). "Nigeria: Poverty in the midst of Poverty", A World Bank Poverty Assessment Report N0 14733 – UNI World Bank (2000). Can Africa Claim the 21st Century, Washington: World Bank World Bank (2001). World Development Report, Oxford: Oxford University Press World Bank (2002). Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook. Washington, DC. World Bank (2005). Summary Week II. Message posted to the Dgroups electronic mailing list, measuring the Impact of Communication in Development Projects and Programs, archived at http://dgroups.org/groups/worldbank/wccd1/index.cfm?op=main&cat_id=9522, February

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=172&layout=html

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||