Adapted from DfES (2001, para 1.12) The report also defines two types of human support needed for implementation of ICT at the school level: (a) technical and (b) in-class curricular (DfES, 2001, para 5.24). This distinction has also been noted by Sandholtz (2001) and other researchers in the UK. In contrast, this kind of distinction, is rarely if ever mentioned in the literature from Hong Kong.

Reviews in Hong Kong In the reports published by the Hong Kong government, the implementation of ICT in schools is always described as successful – “The five-year strategy has succeeded in laying a solid foundation for IT in education in Hong Kong” (EMB 2004b). “Five years on, we [the government] have seen tremendous changes to schools as learning institutions: all schools are connected to the Internet; teachers have acquired at least basic skills and embracing IT as a teaching tool; students are using IT and the Internet in project-based learning” (EMB 2004a, Foreword). Not only the Hong Kong government, but also many of the region’s educational researchers, emphasised only positive evaluations of ICT. Any criticisms or dissenting opinions are challenged. For instance, in a study by Li & Chow (2000), an interviewed teacher questioned the pedagogical usefulness of ICT. I’m a bit uncertain that ICT can really help students learn better. Most of the learning experience and learning outcomes being quoted as exemplars can also be achieved without using ICT (reported by Li & Chow 2000, p. 149). In the same paper, another interviewed teacher expressed her helplessness: As I come from an arts background. I know little about computer. Therefore I have to equip myself with computer skills first… then I have to find ways, on my own, to integrate ICT into my teaching(reported by Li & Chow 2000, p. 149). However, the researchers of the study have not attempted to find out the causes of the difficulties experienced by both teachers. Eventually, teachers with complaints were labelled as “reluctant to change” by the researchers (Li & Chow 2000, p. 149). From their point of view, ICT must be good. Any questioning of such technology must be unreasonable. Teachers with different opinions must “reconsider [their] personal attitudes and beliefs…and re-examine their conception of technology’s role….” (p. 150). In Hong Kong, research studies have usually failed to identify the problems of teachers. Li & Chow (2000) and Yuen (2003), among others, blame teachers for problems with implementation. Teachers have been accused of being “reluctant to change” (Li & Chow 2000, p.149) or “inclining to conventional view” (Yuen 2003, p. 160). This unfair, if not biased, attitude toward teachers is typical of Hong Kong’s educational community. In this kind of atmosphere, teachers tend to suppress their feelings because they do not want to be discriminated against or, even worse, fired. The helplessness of teachers, if any, cannot be solved and the real picture has no way of reaching government officials or policymakers. As time has passed, teachers have treated ICT as a burden, instead of a partner, in their teaching. In contrast, a very great difference has been found in the education communities in the UK and elsewhere in the world. Studies by DfES (2001), Gimbert & Cristol (2004), Sandholtz (2001), and Williams, Coles, Wilson, Richardson & Tuson (2000), have been carried out to respond to the problems with, and concerns of, teachers. One of the aims of these studies has been to discern the “true” situation of teachers, instead of blaming them.

Staff Development and Technology Leaders School heads, government officials and the public often like “beautiful packaging”. Many observers of ICT in education confuse good presentation with good pedagogy. Consequently, many external training courses for teachers have focused on the acquisition of operational skills. In a study of ICT policies in New Zealand, Lai (2001) found that professional development programmes commonly over-emphasized “skill-based” training at the expense of “consideration on pedagogy of ICT” (pp. 345-346). Many research studies suggested that peer mentoring provided by school-based technology leaders could be a good alternative to external “training” programmes. The administrative leader of a school in the UK is often known as the headteacher, which is the equivalent of principal or headmaster/headmistress in Hong Kong and different parts of the world. In the discussion of technology in schools, technology leaders also have an important place. Technology leaders should possess not only technical but also pedagogical competency. Wood (2003) emphasized the importance of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for teachers, particularly in the proficiency in educational technology. He built a four-level ICT proficiency model, starting from the awareness level to the highest fluency level. Similarly, Moursund (1997b, pp. 4-5) defined an eight-level “Stages of Concern” model from the “awareness” level to the “leadership” level, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Stages of acquisition of IT knowledge for educators

Compiled with information from Moursund (1997b, pp. 4-5) Teachers who have reached Stage 8 are considered technology leaders. They are “faster” learners of ICT and have the characteristics of leadership in technology. Moursund (1997a) encourages teachers to take professional development and become “high-level leaders” (p. 4). Those leaders are able to help “slower” colleagues make optimal use of ICT in their classrooms. This gradual development in technological skills among teachers was also observed by Tearle (2003). Although Tearle’s study focused on a secondary school, some of its findings could be applicable to other levels of the educational system. The school in his study adopted a “staged” approach in its development of ICT. That is, “ICT development started off in a small way and gradually built up,” emphasizing a “natural grouping of departments” (Tearle 2003, p. 576). As facilities became available, more departments were invited to join the ICT implementation program. Strong departments, those with an enthusiastic and capable staff, started first. Soon after, “the resulting positive outcomes, evident for others [departments] to see, created a climate where the implementation of ICT was seen as desirable” (Tearle 2003, p. 576). This staged approach has an advantage: the ICT coordinator is able to undertake a “manageable task.” In other words, “by focusing on one or two departments at a time, it has been possible to attend to their specific needs and address difficulties as they arise; hence improving the likelihood of success and positive response from those involved” (Tearle 2003, p. 576).

THE ROLE OF ICT COORDINATORS In the UK, ICT coordinators in schools are also regarded as leaders. In any successful school, “it is almost exclusively due to the strong leadership of the headteacher and ICT co-ordinator” and “ICT co-ordinator is the driving force behind improvements in the school’s ICT teaching and learning” (OFSETD 2002b, para 13). In a study in the US, Ronnkvist, Dexter & Anderson (2000) also suggested that technology coordinators should have the leadership and administrative capacities as follows: Technology support programs are more effective when directed by well-trained technology coordinators… technology coordinators must be trained to bridge technical ability with classroom teaching experience; their leadership and administrative capacities should be nurtured; and their aptitude for instructional design should be developed (p. 26). Both the school head and the ICT coordinator are joint leaders in implementation of ICT, although they have different roles in the implementation. Unfortunately, in Hong Kong, school-based ICT coordinators are usually not given this status. Although the EMB (2004b) mentions leadership of technology in schools many times, it does not link the ICT coordinator with leadership. This is an interesting difference in the mindsets of the policymakers in Hong Kong and the UK. Even worse, ICT coordinators are frequently treated as technical support staff in many schools in Hong Kong (Yuen & Lee 2000). Reports from OFSTED in England cite the importance of the skill level of teachers as an essential factor in facilitating good ICT use in schools. “In far too many schools, however, “the training has disappointed teachers and has failed to meet their needs, whatever their level of ICT expertise” (OFSTED 2002b, para 18). The main problem was that most training programmes had not been tailored to teachers at different levels of competence – which is a common failure of the “one-size-for-all” training courses. The training had “not met the pedagogical need of teachers” in half of the visited schools (OFSTED 2002b, para 18). In turn, insufficient training and, consequently, lack of confidence were suspected in leading to an “underdeveloped” use of ICT in a school (OFSTED 2002b, para 19). Eventually students’ progress in using and applying ICT was restricted. Two years later, OFSTED reported that there have been some, though insufficient, improvements in the “quality of teaching using ICT”. However, some teachers are still not ICT-competent enough to challenge their students. The implication is that teachers are not able to stimulate their students for the same reason (OFSTED 2004, p. 8). This point, that some teachers are not confident enough to handle students who might have greater ICT capability, matches Elliot’s (2001) report cited in previous section. The same OFSTED (2004) report claims that technical support at the school level rarely matches the demand due to rapidly increasing deployment of hardware and software. This deployment is outpacing the increase in technical support and creating problems for teachers. This report also states the problems with teachers’ ICT. Complaints have been made against the majority of training, including the New Opportunities Fund (NOF) training, which has been badly designed and carried out. In return, “much training made a limited contribution to their [teachers’] awareness of subject-specific ICT applications and did not encourage them to consider issues of teaching and learning with ICT”. (OFSTED 2004, p. 22) Williams et al. (2000, p. 319) suggest that “training alone” for teachers might not enhance the use of ICT in schools. Training should be “appropriate in terms of skills, knowledge, relevance to educational goals and priorities, and delivery” (p. 319). Provision of a localised and supportive environment is important in a “holistic approach” to enhance the use of ICT in schools. As pointed out earlier, school-based technology coordinators, who are supposed to have strong competence in both ICT and pedagogy, should be able to determine the most suitable development for teachers. They can train and mentor other teachers. However, this kind of role for technology coordinators is not generally reported or observed in Hong Kong primary schools. After all, the contribution of technology coordinators will be an interesting question to be studied in the “mini-survey” that is described in the forthcoming section.

METHOD The study in the current paper examines ICT from the perspectives of school heads and teachers, who presumably play the most critical roles in schools. This paper extracts and reports the findings from a larger scale study which made use of a cross-sectional self-administered questionnaire. Including the demographic section, there were 39 close-ended questions and one open-ended question in the original study. This paper focuses on a question which is directly relevant to ICT coordinators. Important findings from other questions will be presented and/or published by the author in other venues. In Hong Kong, a complete list of primary schools and their heads is available online to the public. The author used this information to collect the names and contact information of all the heads as the sampling frame. In the UK, a single list of all primary schools or headteachers was not available. Instead, separate lists of schools with headteachers in certain counties, boroughs and cities were available online from their regional councils. These were a good source for approximating a “multi-stage cluster” (Clark-Carter 2004, pp. 156-157) sampling strategy. Finally, lists of primary schools in Leicester, Leicestershire, Northampton and Manchester were defined as the sampling frame and retrieved. Heads within the sampling frame were selected systematically. Eventually, questionnaires with covering letters were faxed to the selected school heads in HK and UK. Participants returned their responses by fax, which were forwarded to the author’s e-mail box. Due to logistical constraints, teachers in England were not covered in this study. Because a list of all primary teachers in Hong Kong was not available, another portion of the questionnaires was delivered and collected face-to-face at educational conferences, forums, and seminars. On such occasions, primary teachers from different disciplines and different levels congregated. The overall response rate reached 62%, which is generally considered to be a “good” level by Babbie (2001, p. 256).

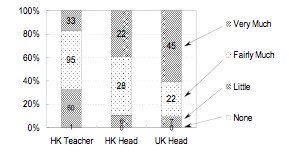

DATA ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS The respondents of the survey are categorised into three subgroups: HK Heads, HK Teachers and UK Heads, representing school heads and teachers from Hong Kong, and heads from England, respectively. They are requested to respond to the following question: How much does the ICT coordinator contribute to your school ? 1. Very Much 2. Fairly much 3. Little 4. None The responses from the subgroups are presented in Table 3. The greatest proportion (62.5%) of UK Heads described ICT coordinators (ICTC) as contributing “very much” to teaching. In contrast, only a small proportion (17.4%) of HK Teachers rated ICTC as having “very much” contribution. A fair proportion (39.3%) of HK Heads rated ICTC as making “very much” contribution.

Table 3: Rating from subgroups of respondents

On the other hand, a relatively high proportion (31.8%) of HK Teachers rated ICTC as making only “little” contribution and one HK Teacher rated ICTC having no contribution at all (“none”). On the other hand, few HK Heads (10.7%) rated ICTC as having “little” contribution. Also very few UK Heads (9.7%) rated ICTC in this category. Table 3 shows that UK Heads tended to rate “very much” more than other subgroups did. To visualise a major difference in their views, the ratings of “fairly much” and below are consolidated and graphed side by side with the rating of “very much”, producing a interesting result as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Perceived contribution of ICT coordinators

Figure 1 clearly shows that the subgroup “UK Heads” has a more positive view of the contribution of the ICT coordinators. In order to confirm the difference among the views represented in the three subgroups, inferential statistics are applied to the “very much” rating. In the current analysis, the “very much” rating is coded as “1” and other ratings below that are coded as “0”. The null hypothesis is that the mean ratings of “very much” of a contribution from different subgroups of respondents are equal, i.e.

Table 4: ANOVA results of the subgroups

The One-way ANOVA test results, as in Table 4, show that the null hypothesis, Table 5: Multiple pairwise comparisons with Tukey HSD test

The test results further confirm that remarkable differences exist among three subgroups. Finally the attitudes of the contribution of ICT coordinators rated by the three subgroups of respondents were found in the following order: It emerged from the survey that HK Teachers and HK Heads did not rate ICT coordinators’ contributions, as highly as their UK counterparts did. There might be a problem of “under-utilisation” of ICT coordinators in Hong Kong’s schools. In the next section, some approaches in refining the role of ICT coordinators will be recommended for an overall enhancement of teaching and learning.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND DISCUSSIONS Certain studies suggest that human factors should be heavily weighed in the development of educational technology. Wahl’s (2000) study, for example, states that 70% of the budget should be spent on “human infrastructure” (p. 7) and only 30% should be spent on equipment. The human infrastructure should incorporate the basic ingredient of staff development. Unfortunately, schools and authorities often prefer purchasing tangible goods, such as hardware and software, with their limited budgets (Ringstaff & Kelley 2002). ICT coordinators should be considered an important asset. However, their “leadership” roles, although highly regarded in the UK, are often ignored in Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, the duties of ICT coordinators sometimes overlapped with those of technical support staff. There was no evidence that the launch of the ICT coordinator scheme in Hong Kong was well-planned. It created unclear definitions of the role of ICT coordinators. It is uncertain, for example, whether ICT coordinators are meant to perform operational or pedagogical functions, or both. In contrast, the role of school-based ICT coordinators in the UK is less ambiguous. They are also pedagogical leaders, with few if any technical support duties. In one school in the UK, for example, “the ICT coordinator was established freedom to plan ICT activities and draw in staff as appropriate” (Lawson & Comber 1999, p. 48). To optimise their contributions, ICT coordinators in Hong Kong should also established with similar professional respect and trust accorded by their schools. Alessi and Trollip (2001) argued that ICT is sometimes, but not always, the best solution for teaching. Other mediums of instruction clearly have their own advantages; “we would sometimes find an advantage for books, sometimes teachers, sometimes film or video, sometimes peer-tutoring, sometimes hands-on field experience, sometimes listening to an audio tape, sometimes computers” (p. 6). In considering instructional media for a particular purpose, other media should not be excluded. Teachers should be able to select the best teaching medium for each subject, because “not all subjects fit to all instructional forms” (Rindermann 2002, p. 325). In this sense, teachers should not be biased in favour of ICT-based media. They should be able to differentiate the suitability of different media and make the most “adequate use of media and programs for selected subjects” (p. 325). In order to do this, any professional development programme should allow teachers to acquire this capability. Gimbert and Cristol (2004, p. 214) criticize the one-size-fits-all approach in traditional training programmes for teachers, because it cannot best address their individual needs. Ideally, teachers at different levels and with different characteristics should receive different types of training, As pointed out by Snoeyink and Ertmer (2001), “different teachers comprise different types of learners who could not be treated the same” (p. 104). In the study by Snoeyink and Ertmer (2001), teachers showed a preference for receiving training in small groups or for direct help from their peers, instead of large group training. Kariuki et al. (2001) also reported that a small group mentoring process was welcomed by school teachers. Some mentees have been found to go through an “observers to co-learners to leader” transition, and finally have gained the confidence to make use of ICT in their own teaching (p. 416). However, in Hong Kong, training programmes are frequently designed and conducted in a “skill-based” mode. Teachers are often expected to produce attractive presentations using the “skills” learned in these “training” courses. Staff development may place more emphasis on school-based training instead of the internal peer-mentoring model that may be more relevant to teaching. ICT coordinators with strong technological and pedagogical proficiency would be the ideal in filling this role. Staff development with reference to the staged approach (Tearle 2003), being led by a technology coordinator, could be an effective strategy.

LIMITATIONS AND EXTENSION OF THE STUDY As stated by Marshall & Rossman (1999), “no proposed research project is without limitations; there is no such thing as a perfectly designed study” (p. 42). This study is no exception. Due to logistical and resource constraints, the survey has only covered heads, and not teachers, working in certain regions in England. The coverage of a wider area and the involvement of teachers in a future study would provide a more complete comparison with school heads and teachers in Hong Kong and England. Views from other parties, such as students and parents, may be equally important but do not fall within the scope of the present study. Further investigations in comparing the competence of ICT coordinators in England and Hong Kong could be a good extension of the current study. Future research might explore their capability of being leaders, and assist in formulating measures for those less competent ICT coordinators to improve themselves. Last but not least, a mixed-method approach could be a fruitful way to collect further data through different channels or in different forms, to cross-verify, or “triangulate”, the outcomes of the current study (Brewer & Hunter 1982; Creswell et al 2004, p. 11). As a complement to the quantitative data reported in this paper, qualitative data have been collected by the author. Analysis of and findings from these data will be presented by the author in future writings.

REFERENCES Ager, R., 2000. The Art of Information and Communications Technology for Teachers. David Fulton, London, UK. Alessi, S.M. & Trollip, S.R., 2001. Multimedia for Learning: Methods and Development (3rd Ed.). Allyn & Bacon, Needham Heights, MA, USA. Babbie, E., 2001. The Practice of Social Research (9th Ed.). Wadsworth, California, USA. Brewer, J. & Hunter, A., 1989. Multimethod Research: A Synthesis of Styles. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA, USA. Clark-Carter, D., 2004. Quantitative Psychological Research: A Student’s Handbook. Psychology Press, Hove, UK. Creswell, J.W., 2003. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. DfEE, 1997. Connecting the Learning Society: The Government’s Consultation Document of the National Grid for Learning, Department for Education and Employment (now Dept. for Education and Skills), London, UK. DfES, 2001. Teacher Workload Study Conducted by PriceWaterhouse Coopers, Department for Education and Skills, London, UK. Retrieved 9 February 2007, from http://www.dfes.gov.uk/pns/pnattach/20010326/1.htm Elliott L., 2001. Doubts over teachers’ computer training, BBC News, 2 April 2001. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/education/1256338.stm EMB, 1998. Information Technology for Learning in a New Era: Five-year Strategy 1998-2003. Education and Manpower Bureau, Hong Kong. EMB, 2004a. Information Technology in Education – Way Forward. Education and Manpower Bureau, Hong Kong. EMB, 2004b. EMB Press Release on 16 March 2004, Education and Manpower Bureau, Hong Kong. Retrieved 9 February 2007, from http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/200403/16/0316118.htm Gimbert, B. & Cristol, D., 2004. Teaching curriculum with technology: Enhancing children’s technological competence during early childhood. Early Childhood Education Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 207-216. Hargreaves, L., Moyles, J., Merry, R., Paterson, F., Pell, A., & Esarte-Sarries, V., 2003. How do primary school teachers define and implement interactive teaching in the National Literacy Strategy in England? Research Papers in Education, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 217-236. Kariuki, M., Franklin, T., & Duran, M., 2001. A technology partnership: Lessons learned by mentors. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 407-417. Lai, K.W., 2001. Role of the teacher. In Adelsberger, H.H., Collis B. and Pawlowski, J.M. (Eds.), Handbook on Information Technologies for Education and Training. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp. 343-354. Lawson, T. & Comber, C., 1999. Superhighways Technology: Personnel Factors Leading to Successful Integration of ICT in Schools and Colleges. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 41-53. Lawson, T., & Comber, C., 2000. Introducing Information and Communications Technologies into Schools: the Blurring of Boundaries. British Journal of Sociology of Education, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 419-433. Li, S.C. & Chow, Y., 2000. Catalytic integration model. In Law N. et al (Eds), Changing Classrooms and Changing Schools: A Study of Good Practices in Using ICT in Hong Kong Schools. University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, pp. 103-113. Luckin, R., 2001. Designing children’s software to ensure productive interactivity through collaboration in the zone of proximal development (ZPD). Information Technology in Childhood Education Annual, Vol. 2001 No. 1, pp. 57-85. Marshall, C., & Rossman, G.B., 1999. Designing Qualitative Research, Sage Publications, California, USA. Moursund, D., 1997a. The future of information technology in education. Learning and Leading with Technology, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 4-5. Moursund, D., 1997b. Professional development – an eight-level scale. Learning and Leading with Technology, Vol. 25, No. 4, pp. 4-5. OFSTED, 2002a. ICT in Schools: Effect of Government Initiatives – Progress Report, April 2002. Office for Standards in Education, London, UK. OFSTED, 2002b. ICT in Schools: Effect of Government Initiatives: Implementation in Primary Schools and Effect on Literacy, June 2002. Office for Standards in Education, London, UK. OFSTED, 2004. ICT in Schools: The Impact of Government Initiatives Five Years On, May 2004, Office for Standards in Education, London, UK. QEF, 2005. Qualification Education Fund: Objective and Scope. Qualification Education Fund, Hong Kong. Retrieved 9 February 2007, from http://qef.org.hk/eng/main.htm?aboutus/aboutus02.htm Rindermann, H., 2002. Evaluation. In Adelsberger, H.H., Collis B. and Pawlowski, J.M. (Eds.), Handbook on Information Technologies for Education and Training. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, pp. 309-329. Ringstaff C. & Kelley L., 2002. The Learning Return on our Educational Technology Investment. WestEd, San Francisco, USA. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http://www.wested.org/online_pubs/learning_return.pdf Ronnkvist, A. M., Dexter, S. L., & Anderson, R. E., 2000. Technology support: Its depth, breadth, and impact in America's schools. Teaching, Learning and Computing: 1998 National Survey, Report #5. Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations, University of California, Irvine and University of Minnesota, USA. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http://www.crito.uci.edu/tlc/findings/technology-support/report_5.pdf Sandholtz, J., 2001. Learning to teach with technology: A comparison of teacher development programs. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 349-374. Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, 1997. The People's Lottery. HMSO, London, UK. Snoeyink, R., & Ertmer, P., 2001. Thrust into technology: How veteran teachers respond. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 85-111. Tearle P., 2003. ICT implementation: what makes the difference? British Journal of Educational Technology Vol. 34, No. 5, pp. 567-583. Tung, C.H., 1997. Building Hong Kong for a New Era, Address by the Chief Executive at the Provisional Legislative Council Meeting on 8 October, 1997. Government Printer, Hong Kong. Vygotsky, L.S., 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, et al, Eds. and Trans.). Harvard University Press, MA, USA. Wahl, E., 2000. Cost, Utility, and Value. Education Development Center, New York, USA. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from http://www2.edc.org/CCT/admin/publications/administrator/abd_cuav.pdf Williams, D., Coles, L., Wilson, K., Richardson, A. & Tuson, J., 2000. Teachers and ICT: Current use and future needs. British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 311-324. Williams, M.D., 2000. Introduction: What is technology integration. In M.D. Williams (Ed), Integrating Technology into Teaching and Learning: Concepts and Application. Prentice Hall, Singapore. Wood, D., 2003. Think Again: Hindsight, Insight and Foresight on ICT in Schools. Report for EUN’s ERNIST project, November 2003 Ed. Retrieved 5 March 2007, from Yuen, A.H.K., 2003. Fostering learning communities in classrooms: A case study of Hong Kong schools. Educational Media International, Vol. 40, Issue 1&2, pp. 153-162. Yuen, H.K., & Lee, Y., 2000. Technology adoption model. In Law N. et al (Eds), Changing Classrooms and Changing Schools: A Study of Good Practices in Using ICT in Hong Kong Schools, pp. 125-138, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=368&layout=html

|