Organizational level: Number of prototypes formulated and integrated Number of prototypes Formulation and implementation are the first steps after the RT workshop. Lessons learnt should be drawn and the prototype can be perfected or revised and be applied on a larger scale. For a prototype to be integrated it is necessary that it is institutionalised, e.g. is part of daily life. However, Kimaro and Nhampossa (2005) remark that only institutionalisation is not sufficient: new practises should also be perceived as generating value to the organization. This is reflected by the prototype being included in the strategy of the organization with resources allocated to it. This largely covers the different stages of ICT implementation (Saga & Zmud, 1994). The competency of the organization to manage the further development of ICT applications is another criterion for full integration. Comparison against an international norm Comparison against a norm places the effectiveness of the RT process in perspective to other practices. It is hard to find a ‘norm. Reports on failures are widespread, but rarely quantified. Heeks (2002) made an effort to develop a norm related to the successful integration of prototypes. He postulates that only a minority of information system projects6 – a concept that includes the ICT prototypes – in developing countries is successful. He categorised ‘failure’ as never implemented or immediately abandoned after implementation. He defined ‘partial failure’ as “an initiative in which major goals are unattained or in which there are significant undesirable outcomes…… or a sustainability failure of an initiative that succeeds initially but then fails after a year or so” (Heeks 2002, p 103). The major goals and the undesirable outcomes are defined by combining the perspectives of the major stakeholders involved. In industrialised countries Heeks estimated for the period up to 2001 that roughly 20-25% is a total failure, 35-60% is a partial failure and the remaining (15%- 45%) can be labelled as a success. Based on different sources, Mann (2002) stated similar success and failure rates for IT projects in education. Other sources point in the same direction (Wade 2004; Dada 2006). We share Heeks’ observation that in view of the weak environment, failure might be expected to be higher in less developed countries. The success rate for the prototypes developed through the RT process needs to be comparable to Heeks’ norm. Impact on users Innovation generates value and also changes the positions of the actors involved (Janszen 2000). Increased empowerment and economic opportunities are therefore main impact categories. The impact, as experienced by the end-user, is first measured through the awareness on the possibilities of ICT. Secondly empowerment is measured through statements based on increased skills levels, more self esteem, status and an increased ability to influence decision making. The economic impact is reflected through increased productivity, more income or better job opportunities. Impact on poverty reduction In a development setting, the main theoretical perspective on poverty is the lack of access to social services and control over resources including knowledge and market opportunities (Narayan, 2000). A first indication is the number of prototypes integrated that are developed by the representatives of the poor. A second indicator is the number of users that can be categorised as ‘poor’7. A third criterion is whether the prototypes contribute to the improvement of the structural conditions under which the poor live e.g. access to primary education. Indirect effects on poverty could be important, but have not been assessed in this study. Stimulating the ICT integration at sector level The sustainability and scalability of ICT applications can be analysed around three factors: (1) the actual demand of the technology, (2) usability of the ICT in the everyday activity of users, and (3) the availability of support services (Mursu et al., 2005). While the value added and usability of the technology is covered by the criteria mentioned above, more is required, especially for a public service sector like education. The development of an ICT policy is needed to assure the development of an adequate educational philosophy, to allocate financial and human resources and to stimulate and regulate the development of supportive services. Therefore agenda setting and policy development are essential. In CTA terms, the integration of the technology at meso or sector levels requires networking to develop a knowledge base.

RESEARCH METHOD The study includes substantial quantitative data on the number of users, the perceived satisfaction on the objectives achieved by the users and the perceived level of impact. Nevertheless, a main part of the research method is qualitative research, in order to understand the meaning and the context of the outcomes, as well as to identify unanticipated influences (Maxwell, 1998). Qualitative research can bring in and confront the perspectives of the different actors involved To select an appropriate project for the evaluation of the RT process the following criteria were used: the project to be studied should (1) be the outcome of a successful RT workshop, (2) be ‘old enough’ to allow a mature view on the second and third development cycle, and (3) have been object of data collection, including participatory observation, right from the beginning. The project that fitted these criteria most was the RT process on ICT for learning and teaching for secondary and teacher education in Tanzania. Different data sources were used: semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, focus groups, participatory observation, desk study and peer review. We elaborate on each data source. An important source was the perception of the participants and some knowledgeable third parties obtained through 12 semi-structured interviews by an independent freelance researcher in 2006. Questions related to the development of the prototypes within the organization, their added value, capacity development and their link to the wider context. The findings were discussed with the prototype owners. To assess the impact on end users and to have feedback on the IICD assistance, the data from the IICD monitoring and evaluation system (M&E) was used. This M&E system was developed by IICD in 2001 and allows for results to be compared between countries (Wieman et al., 2001). Constructs to measure impact were awareness on ICT, empowerment achieved, economic opportunities realized, personal skills and productivity. A closed questionnaire, which measured on a Likert scale from 1 to 7 (see annex 2), was administrated by a M&E consultant and filled in by 191 respondents. During annual focus group meetings, conducted by the M&E section of IICD, the prototype teams reflected on the findings of the M&E system. This included the assessment of the quality of the assistance and capacity building by IICD to the prototype teams. It also included the results of the feedback of the end users on the realisation of their objectives by using the prototypes and on their perceived impact. Another data source was participatory observation by the first author, who was a facilitator and coach in the evaluated project. Possible researcher biases were minimised by reviewing data, findings and conclusions with freelance researchers, team members and some independent national observers. Advantages of participatory participation were an in-depth knowledge of the situation and its dynamics, a better understanding of the irrational and emotional aspects, and the interaction with the context. Important source for participatory observation were the intensive bilateral contacts and regular (every two or three months) joint meetings with all teams working on prototypes. During these meetings the prototype teams exchanged experiences, latest news and discussed specific themes. These conversations were generally marked by a great frankness. Also explicitly solicited was negative feedback Of course also ‘socially desired’ answers were given, but these were minimized through the group process and the long-term relationship that developed. Data collection is complemented by analysis of reports, peer reviews with staff and consultants directly involved in the RT process, in line with the principles for interpretive field studies (Klein & Meyers, 1999). This mix of methods and data sources contributed to triangulation (Maxwell, 1998). Data that converged is reported in this study without reference, if data did not converge, the divergence is elaborated.

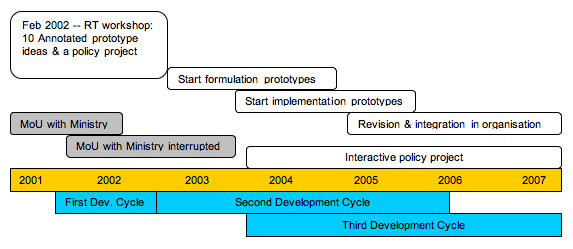

PROCESS CONDITIONS The RT process for education in Tanzania largely followed the sequence of interventions as set out in annex 1. Prototype owners and their teams participated in nearly all interventions. The process was rather intensive the first six months with a workshop on project formulation and training on ICT skills. The process conditions as mentioned in section 4 include the involvement of relevant stakeholders, participation, dialogue, exerting drive by a few actors to maintain the CTA infrastructure and to organize and facilitate the processes of learning, societal agenda development and communicative actions. A network for exchange of knowledge was created by the RT process. It served as a participatory platform and facilitated active exchange between prototype owners and main actors in the sector. The network gradually ‘lost’ representatives of the Ministry as political constraints emerged. This was triggered by a corruption scandal around a gift of ten thousand refurbished computers by a Northern donor, public upheaval as a number of telecenters stimulated visiting pornographic sites by students and uncertainty within the Ministry about the financial and managerial implications. As a consequence the memorandum of understanding was terminated by the Ministry. This slowly reduced the network8 and minimised communication between the prototype owners and policy makers. The network carried out awareness-raising sessions to the large public, and lobbying sessions towards the politicians and the Ministry. At sector level, networking and advocacy were insufficient to put ICT in education on the political agenda. Therefore a participatory multi-stakeholder intervention was designed and implemented. It should be noted that users were involved in the development of the idea of the prototype during the RT workshop, but that only 50% of the prototypes involved the users in the formulation stage. Later on user feedback was obtained – more passively – through questionnaires. The CTA agent (IICD) played multiple roles embodied by different persons. The programme manager focused on coaching, facilitation and networking. He separated the roles during interaction and had a relationship of trust with the prototype owners. Role conflicts were not put forward in interviews, nor experienced as problematic by the interviewees. Coaching is a delicate process, especially in an environment with an overwhelming donor culture. The IICD training manager provided technical expertise. Both were experienced and attached value to local ownership as the ‘sine qua non’ to success. Consultants, however, tended to infringe on dialogue and ownership. For example a consultant assisting in the formulation of mobile teacher training resource centres gradually distorted the project towards training in management information systems; an area he was acquainted with. The basic argument was sustainability, yet the ‘owners’ intended rather to support teaching and learning processes. The influence of expert power made them give in. Conflicts about financing were minimized as simple and clear rules were applied and a final decision depended on the outcome of a peer review within IICD. The prototype owners found the prototype formulation process useful and stated that much learning occurred. It strengthened their capacity to conceptualise and to implement. The interviewees indicated that the prototype formulation process strengthened their sense of ownership, including motivation, and boosted their self-confidence. Statements by owners during focus group sessions were:

However, they also criticised. For example, they pointed out that training on financial management and marketing/lobbying should have been included much earlier. Coaching stimulated alignment, collaborative decision making and institutionalization at organizational level. The potential synergies between the prototypes were clearly acknowledged and resulted in some collaboration. However, the initiative to create a consortium for a stronger market position towards donors, other NGOs and the Ministry did not work out due to insufficient mutual trust.

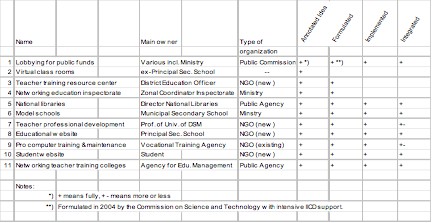

OUTCOMES Below we describe the outcome indicators as categorized in section 4. Organizational level: Number of prototypes formulated and integrated The RT workshop yielded eleven annotated prototype ideas, including a policy project. One of the prototype ideas, the virtual class rooms, was dropped as little time was available for its development and acceptance was anticipated as low as criticasters remarked

Another prototype, teacher training center, never got funding. Due to the political constraints, one prototype had to be stopped (# 4, Table 2) and the development of two other prototypes slowed down (#5 and #11).Eight were implemented (see Table 2).

Table 2: Overview of prototypes according to their stage of development at organizational level

Seven of the eight implemented prototypes received funding9. Most prototypes started in 2002/ 2003, one in 2004 and one in 2005. The prototypes accomplished their objectives within the budget set. About four years later (June 2006), seven prototypes were still operating, albeit with objectives and functioning updated. In general, each organization had achieved its intended output in terms of the service or product to be developed. One NGO had to close late 2006 as it suffered from misuse of funds and bad debts, although it fulfilled most of its objectives. The prototype for the National Libraries could not secure external finance over a long time. When a new manager came, it was picked up again and implemented on a larger scale from internal funds. The successful integration of this prototype can therefore only be partly attributed to the RT process. The prototypes or projects within existing organizations were well integrated. Especially the prototype of the teacher training colleges scored strongly on the indicators for being integrated. Key aspects of success included the strong participation of all principles and their deputies in the overall process. An enlarged programme is now financed by a bilateral donor. The model school integrated ICT in teaching, planning and administration. It was largely financed out of its own meagre budget. The NGOs struggled to mobilise financial resources in the market. Their skills and drive to earn money in the market were moderate, but increased over time. The purchasing power of customers was low and education – like health services – used to be a free good. Moreover, it was hard to obtain public financing as public-private partnerships were not an established concept. The competences of staff members were for all prototypes sufficient to sustain and upscale activities, though weak on commercial insight. Some problems were more of an organizational nature as the NGOs progressed to a more mature stage. Two out of three NGOs were dynamic in the sense of developing and pursuing additional ideas to enrich their services. Besides the specific financial problems for the NGOs and based on the outcome indicators (Table 1) by June 2006, we conclude that five out of the eleven annotated prototype ideas are fully integrated at the organizational level and two partly. The interactive policy process was successful, but is discarded from this list as it is not a prototype. This implies that the RT process scores slightly above the norm advanced by Heeks (2002), on the number of successful projects. Impact on users Estimated user data as of inception till mid 2005 are presented in Table 3. This was based on estimates per prototype, which included management and a subject matter specialist. The findings were validated during a meeting with all teams. Estimates were made carefully and provided an indication of the order of magnitude. Most decision makers in the Ministry and most users in teacher training colleges were reached. With a total number of students of secondary schools estimated at about 300,000 in 2003 (O-saki & Njabili, 2003), also the outreach to this group was substantial. Table 3: Estimated number of users per prototype (from the start of prototypes up to mid 2005)

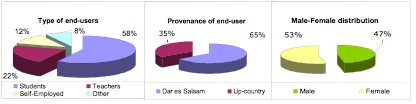

A survey (n=191) in 2005, among end-users of a number of prototypes indicated a frequent usage of the services. Satisfaction was high and 90% of the end users stated to have achieved their goals. Details are provided in Figure 2. The bias towards the capital city was a consequence of differences of awareness, the willingness to pay for the services and the fact that the prototypes were developed in the capital city. However, the end users of the educational website in the rural areas had not been reached in the survey, which meant an overestimation of the ‘capital city’ bias.

Figure 2: Background data on end users The criterion for a positive impact is defined conservatively, if the average for the aggregated constructs equals 5.5 or higher (on a scale of 7, see annex 2). On impact, 64% of the end users agreed, or strongly agreed to have an increased awareness on ICT through the prototypes. 45% of the end users stated to be empowered through the prototype. It should be noted that the score on increased knowledge was higher than empowerment as a whole. The moderate economic impact of 44% could be expected in view of the time lag between being a student and having a job. Also the cost involved in using ICT was a considerable burden. Teachers scored a bit higher on economic impact as compared to students. The effect of ICT by reducing transaction costs (e.g. exam results on line) was not captured by the questionnaire on impact, and the usage of this kind of services was very high (over a million hits a month when the exam results were there)10. Since 2002 no major new initiatives on ICT for secondary and tertiary education had been started, besides the e-School programme, an initiative of the Swedish Agency for International Development Cooperation (SIDA) in 2005 and the ICT for teacher training colleges financed by SIDA which incorporated the corresponding prototype. Both drew largely on the prototype owners. Also the development of local content was still limited to the IICD supported NGOs. No other initiatives were undertaken, however the education website was copied by public agencies. Therefore we might conclude that the impact can be largely ascribed to the RT process, though other influences, like the mass media, played a role in creating awareness. However the latter did not seem to result in concrete actions. Impact on poverty Only one representative of the poor participated in the RT workshop; the headmistress of a secondary school. This school was located in a poor urban area and attracted kids from parents that mostly classify as poor (e.g. petty traders). ICT was appreciated by the students and increased their skill level and access to information. Already for more than three years, they sustained the prototype through some contributions of parents and students, but mostly by allocating a part of their tight operational budget to it. Other prototypes targeted a wide audience and could have had a direct or indirect impact on poverty alleviation, especially by providing access to educational materials, knowledge and information, e.g. exam results, and by lowering transaction costs for this type of information. 86% of the respondents of the impact questionnaire indicated to have an average household income. This experience showed that, although there was a strong representation from up country, ICT became urban biased and geared to the higher and middle-income groups, at least in its initial stages. Integration of the innovation at sector level The networking of the prototype owners was a driving force of ICT in the sector through knowledge exchange and awareness creation (demonstrations, media attention, conferences), both in the rural areas, but especially in the capital, Dar es Salaam. Awareness raising and networking with the Association of Headmasters strongly contributed to the establishment of fully operational and cost-effective computer labs for most secondary schools in Dar es Salaam by 2006. The impact on the sector and the importance of the contribution of the RT process and especially the prototype owners to the e-school programme was fully acknowledged by the bi-lateral donor concerned, who perceived it as essential to their mission. The prototype owners brought in knowledge on why it is useful to integrate ICT in secondary education and teacher training, and how to do it. They embodied a vision of a more student-centred teaching and learning process. With more recognition of the importance of ICT in education and this large bi-laterally financed programme to introduce ICT in secondary schools on the brink to be launched, there were new business opportunities for ICT in education. However, political and institutional intricacies delayed this process considerably. The prototype owners developed good relationships with most seniors of the Ministry of Education, but failed to convince the top. Their prototypes stimulated similar initiatives in government institutions, for example the development of an official website of the Ministry and publication of the exam results on the web were clear reactions to the prototypes. However as the government officials pulled out of the network developed in the RT process, new modes had to be found to allow for exchange. Therefore an interactive policy-making trajectory was developed. It started in mid 2003 and resulted in a pre-white paper that was appreciated by the Ministry. August 2007, an ICT policy in education was officially accepted. By mid 2008, funds started to become available from the national budget to introduce computers at public secondary schools. It should be noted that few ministries in Tanzania have an ICT policy in 2008. The network of prototype owners paid ample attention to involving the media. These communicative actions, together with tangible results, awareness raising and advocacy, have speeded up the introduction of ICT in education in Tanzania.

DISCUSSION The ICT project on education in Tanzania showed that the CTA infrastructure as operationalized in the RT process functioned well, but initially less for policy making. The outcomes showed a generation of prototypes of ICT applications that develop novel ICT-based practices, that are replicated, that have a positive impact on end-users and a large outreach. Yet the direct impact on poverty was limited. About 60% of the prototypes was integrated successfully11. If we consider all annotated prototype ideas, this dropped to about 50% by end 2007, mainly due to the institutional barriers, which prevented financing of public services of NGOs from public funds. To put these findings into perspective, the outcomes are firstly compared to other RT processes that were conducted in Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Ecuador, Mali, Uganda and Zambia. In these cases successful RT workshops at sector level were held prior to 2004. Two intervision sessions with members of IICD country teams and IICD’s M&E section were conducted and specifically focussed on sharing lessons learnt from the cases. Applying the RT approach was a learning process within IICD. This learning was reflected, among others, in the increased number of effective RT processes. Out of the annotated ideas generated by properly executed RT workshops at the sector level, about 70 % was formulated, which was slightly higher than the project on education in Tanzania. Achieving formulation was largely a result of the ‘drive’ of the owner and the quality of the facilitation. The number of prototypes implemented as a percentage of those formulated, increased to 90%, which was largely a result of a better RT process, including coaching skills of programme managers. Of the formulated prototypes, about 89% was implemented. Integration was slow and took generally four to five years after the start of the implementation. In this time span, 13% of the prototypes failed to integrate and 31% of the prototypes needed more time to integrate. 45% of the prototypes succeeded to integrate and were considered to have achieved their objectives without an excessive budget overrun. Compared to the norm proposed by Heeks (2002), the level of failure is lower. The level of success of the prototypes generated through the RT process is substantially higher. Heeks found for the industrialised economies up to 2001 about 30-45% being successful. The RT process resulted in 45% of the prototypes successfully integrated. Some prototypes need more time for integration. If the proportion that integrates successfully remains similar, the success rate may rise well above 55%, which would then be a convincing difference over the external norm constituted by the findings of Heeks (2002), especially in view of the environmental challenges in a low resource setting. The impact on end users of other RT processes12 on education was also positive. The direct impact on poverty was weak in the evaluated project. Experience from other RT processes indicated that impact on poverty alleviation was increased by including more representatives of the poor in the RT process and more intensive coaching and capacity building afterwards. Literature also shows that ICT interventions can have a positive effect on poverty alleviation (Cecchini & Scott 2003; Spence 2003; Swaminathan, 2003, p.214). Strengthening the capabilities of the representatives of the poor, prior to the start of the RT process, could possibly enhance the impact. Other measures could be to make negative consequences of certain structural features explicit by the RT participants during the RT process and to include them in the agenda for the interactive ICT policy sessions for the sector or for the national poverty alleviation strategies. Another line of action is increased access to knowledge for empowerment and lower transaction costs.

As mentioned before, the ICT project on education in Tanzania is somehow a special case, as generally neither new organisations are established as a result of the RT workshop, nor is political resistance so ad hoc and strong. It is not related to the country. Another sectoral RT workshop was on ‘ICT for affordable and well-managed district health services’ (Moens et al., 2008b) and held in Tanzania in February 2005. Ten annotated ideas on prototypes were generated, of which seven were implemented by the end of 2006. No political opposition is encountered and replication or up-scaling of prototypes has started.

CONCLUSIONS We conclude that the RT process has contributed substantially to innovating with ICT in the education sector in Tanzania. Findings of other cases point to better results as the complexities of the establishment of new NGOs are avoided. The results in terms of successfully integrated ICT applications are above the norm advanced by Heeks (2002). The RT process can be labelled as successful on the criteria of integration at organizational level, impact for users, and increased speed of overall innovation processes with ICT at sector level. CTA proves to be a fruitful approach to technology development, which triggers ICT-based innovations in the local context. It allows at the user side the domestication of the (radical) innovation. It enables through participatory processes, integration of contextual and apparently ‘irrational’ behavioural considerations into the design of the application of the technology. Sense making and ownership are key factors for individuals and organizations to develop and exert sufficient drive for the implementation of the ICT-based innovations. This aligns with earlier observations (Moens et al. 2008a). In conclusion this CTA based methodology is an interesting approach to ICT design in developing countries. Lessons learnt and areas to improve are the following: The impact on end-users is positive, but their input in the process of the co-construction of the technology could be stronger. Also, the direct impact on poverty alleviation was limited. Looking at other RT processes, we argue that this lack of impact is due to the less optimal implementation of the RT process in the education sector in Tanzania. ICT is a window of opportunity for poverty alleviation. It creates opportunities for most actors and such a ‘win-win’ situation enables to negotiate a redistribution of control over resources. Using opportunities for poverty alleviation requires the right applications, which only can be moulded with a major input of the poor themselves, concerted action, the right timing (Chambers 1983, p.159) and political will. While the RT process is rather effective at organizational level, it is less so at sector level. Collaborative decision making and policy development are areas not yet fully understood. An observation is that decision making at this level is less expedient than appears at face value, but rather is a part of a political and institutional seamless web with limited ‘room of manoeuvre’ and major uncertainties for the actors involved. A paradox emerges as novelty is easier generated by outsiders (Raven, 2005), but less accepted by the established actors. Therefore a pertinent research question is: What influences the scalability of ICT applications that are novel to the local context? Institutional change is essential for radical innovations to assure sustainability and scalability (Braa et al., 2004). The CTA approach to influence institutional change at sector level proved valid, but the nature of institutional change related to ICT needs further exploration.

Acknowledgements Special thanks go to Dr. F. Tilya, who as a freelance researcher interviewed the RT participants and knowledgeable outsiders. The challenging and enriching discussions with the IICD colleagues were appreciated. In the end this is the outcome of a joint experience. REFERENCES Argyris, Ch. & Schön, D.A. 1978, Organizational learning: a theory of action perspective, Addison-Wesley, Reading (Ma). Broerse, J.E.W. 1998, Towards a new development strategy: How to include small-scale farmers in the technological innovation process, Eburon, Delft (NL). Boczkowski, P. J. 2004, “The Mutual Shaping of Technology & Society in Videotex Newspapers: Beyond the Diffusion and Social Shaping Perspectives”, The Information Society, vol. 20, pp. 255-267. Braa, J., Monteiro, E. & Sahay, S. 2004, “Networks of action: sustainable health information systems across developing countries”. MIS Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 337-362. Bütschi, D. & Carius, R. & Decker, M. & Gram, S. & Grunwald, A. & Machleidt, P. & Steyaert, S. & van Est, R. 2004, “The Practice of TA; Science, Interaction, & Communication”. In Bridges between Science, Society & Policy: Technology Assessment- Methods & Impacts, eds. M. Decker & M. Ladikas, pp. 13-55, Springer, Berlin. Cecchini, S. & Scott, Ch. 2003, “Can information and communications technology applications contribute to poverty alleviation? Lessons from rural India”. Information Technology for Development, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 73-84. Chambers, R. 1983, Rural development, putting the last first, Longman Group, Essex (UK). Dada, D. 2006 “The Failure of E-Governance in Developing Countries: A Literature Review”. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 1-10. M. Decker, M. & Ladikas, M. (eds.) 2004, Bridges between Science, Society & Policy: Technology Assessment- Methods & Impacts, Springer, Berlin. Downey, G. L. 1995, “Steering Technology Development through Computer-Aided Design”, In Managing Technology in Society, The approach of Constructive Technology Assessment, eds. J. Rip & T. J. Misa & J. Schot, pp.81-110, Cassell Publishers, London. Furuholt, B. & Ørvik, T. U. 2006, “Implementation of IT in Africa: Understanding and explaining the results of ten years of implementation effort in a Tanzanian organization”. Information Technology for Development, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 45-62. Guston, D.H. 1999, “Evaluating the first US consensus conference: The impact of the citizens’ panel on telecommunications & the future of democracy”. Science, Technology & Human Values, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 451-482. Heeks, R. 2002, “Information systems and developing countries: failure, success & local improvisations”. The Information Society, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 101-112. Heiskanen, E. 2005, “Taming the Golem – an Experiment in Participatory & Constructive Technology Assessment”. Science Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 52-74. ICT op Schools Foundation 2006, Dutch ICT-Tools for a balanced use of ICT in the Netherlands, Rijswijk, (Nl). http://onderzoek.kennisnet.nl/vierinbalans/ Irvin, R.A. & Stansbury, J. 2004, “Citizen participation in decision making: Is it worth the effort?” Public Administration Review, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 55-65. Janszen, F. 2000, The age of innovation: Making business creativity a competence, not a coincidence, Prentice Hall, London. Kimaro, H. C. & Nhampossa, J. L. 2005, “Analyzing the problem of unsustainable health information systems in less-developed economies: Case studies from Tanzania & Mozambique”, Information Technology for Development, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 273-298. Klein, H.K. & Meyers, M.D. 1999, “A set of principles for conducting & evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems”. MIS Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 67-94. Kraft, P. & Bansler, J. P. 1994, “The Collective Resource Approach: The Scandinavian experience”. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 71-84. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester (UK). Mann, J. 2002, “IT education's failure to deliver successful information systems: Now is the time to address the IT-user gap”. Journal of Information Technology Education, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 253-267. Mansell, R. & When, U. (eds.) 1998, Knowledge Societies; Information Technology for Sustainable Development, For the United Nations Commission on Science & Technology for Development, Oxford University press, Oxford (UK). Maxwell, J.A. 1998, “Qualitative research design: an interactive approach”. In Handbook of applied social research method, eds. L. Bickman & D. Rog, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (California). Moens, N.P. & Broerse, J.E.W. 2006, “Innovating in sectoral governance & development with ICT: Conceptualising the ICT Roundtable process”.Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics & Informatics, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 33-40. Moens, N.P. & Broerse, J.E.W. & Bunders, J.F.G & Janszen, F. 2008a,”Information and Communication Technology development in Tanzania: a case study of innovation processes, “International Journal for ICT and Change Management, vol 3, no. 1, pp. 33-62. Moens, N. P., Gast, L., Broerse, J. E. W. & Bunders, J. F. G. 2008b, Initiating a Constructive Technology Assessment approach to ICT planning in Developing Countries: Evaluating the Roundtable workshop, (Submitted). Mursu, A., Tiihonen, T., & Korpela, M. 2005, “Contextual issues impacting the appropriateness of ICT: Setting the stage for socio-technical research in Africa”. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Working Conference of IFIP WG 9.4, Enhancing Human Resource Development through ICT , eds. A. O. Bada & A. Okunoye, pp. 348–358, Abuja: Nigeria. Narayan, D. 2000, Voices of the poor: can anyone hear us? World Bank Publication, Oxford University Press, Oxford (UK). O-saki, K.M. & Njabili, A.F. 2003, Secondary Education Sector Analysis, Ministry of Education & Culture, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Puri, S. K. & Sahay, S. 2007, “Role of ICTs in Participatory Development: An Indian Experience”. Information technology for Development, vol.13, no. 2, pp. 133-160. Saga, V.L. & Zmud, R.W. 1994, “The Nature & Determinants of IT Acceptance, Routinization & Infusion”, In Diffusion, Transfer & Implementation of Information Systems, ed. L. Levine, pp. 67-86, North Holland Publishers, Amsterdam. Schot, J. 2001, “Towards New Forms of Participatory Technology Development”. Technology Analysis & Management, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 39-52. Schot, J. & Rip, A. 1996, “The Past & Future of Constructive Technology Assessment”, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, vol. 54, pp. 251-268. Senge, P. 1990, TheFifth Discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization, Doubleday, New York. Rowe, G & Frewer L.J. 2004, “Evaluating public-participation exercises: A research agenda”. Science, Technology & Human Values, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 512-556. Spence R. 2003, Information & communications technologies (ICTs) for poverty reduction: When, where and how? International Development Research Center, Ottawa, (Canada). Swaminathan, M.S. 2004, “Myths, Realities & Development Implications, panel discussion 6.2 on ICT for Poverty Reduction”, in ICT4D – Connecting People for a better World, eds. G. Weigel & D. Waldburger, Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation and the Global Knowledge Partnership, Bern (CH). Tilya, F. & Moens, N. & Ducastel, N. 2006, ICT in education: The Tanzanian experience. Internal paper International Institute for Communication & Development: The Hague (NL). Tuijnman, A.C. & Brummelhuis, A. C. A. Ten, 1993, Predicting computer use in six systems: structural models of implementation indicators, Pergamon Press, UK. United Nations Development Programme 2005, ICT Socio-Economic Feasibility Study; Socio-economic feasibility study on ICT connectivity & services in three selected areas in Tanzania, UNDP Office, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. UN Millennium project 2005, “Innovation: Applying Knowledge in Development”, Task Force on Science, Technology, & Innovation, United Nations, New York. Van Ryckeghem, D. 1995, “Information technology in Kenya: A dynamic approach”. Telematics and Informatics, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 57– 65. Wade, R.H. 2004, “Bridging the digital divide: new route to development or new form of dependency”? in The social study of information & communication technology; Innovation, actors, & contexts, eds. C. Avgerou, C. Ciborra & F. L&, pp.185-206, Oxford University Press, Oxford (UK). Walsham, G. & Sahay, S. 2006, “Research on information systems in developing countries: Current landscape & future prospects”. Information Technology for Development, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 7 – 24. Wieman, A. Gast, L. Hagen, I., van der Krogt, S. 2001, Monitoring and Evaluation at IICD; an Instrument to Assess Development Impact & Effectiveness, Research Report No 5, International Institute for Communication & Development, The Hague (NL).

Endnotes 1 The Technology Assessment – Methods and Impacts (TAMI) represents an effort by 13 European institutes to explore the major issues of TA in Europe and to draw conclusions on a common TA “reference system” using the “twin group principle”. They considered their effort successful. In their study they added communicative actions as part of TA processes. 2 ICTopSchools is a NGO, supported by the Dutch Government to provide advice, professional support and to monitor progress on the use and beneficial effects of ICT in education. Tuijnman and Brummelhuis developed the principles of the approach, which were refined over time and subject of several PhD studies. 3 The term prototype is used to indicate a first functional version of a new ICT application in that local context. This evolutionary development approach is more commonly used than methods of ‘rapid prototyping’, in which a prototype is developed and after testing, replaced by a larger scale and fully functional version. 4 Most prototypes were financed by IICD and bilateral donors. 5 This analysis is published separately (Moens et al., 2008b). 6 Heeks (1999, p.15) defines information systems as “systems of human and technical components that accept, store, process, output and transmit information”. 7 The international criterion of the poverty line is a dollar a day. Tanzania is one of the poorest countries with a GDP of US $ 221 per capita (2003). The criterion used is the Tanzanian national basic needs poverty line. Around 37% lives below this line. Although the percentage decreases very slowly, the absolute number still increases. Though not exhaustive, it is sufficient an indicator within the scope of this paper. 8 The network was slowly reduced to prototype owners, two interested NGOs, some members of university, the ICT industry and a financial-legal advisor. 9 Funding was through IICD (own funds, or through brokerage with the UK Department of International Development (DFID) and the Swiss Development Cooperation (SDC)) 10 The concern for access to negative content was definitely a reason for a number of parents not to allow their children access to Internet, or only if filtering was done. 11 This corresponds to annotated prototype idea #5, #6 and # 11 as successful and # 2 and # 4 as failure (table 3). 12 The total sample is as follows: Bolivia: 26%, Burkina Faso: 5%, Ghana: 12%, Tanzania: 35%, Uganda: 23%. The impact on end users was higher in other RT processes on education. Possible explanations are the socialist background of Tanzania with a culture of ‘being provided’ and being less competitive, the lower economic level of development and less importance attached to education yet.

Annex 1: Ideal type of process steps in the RT process

Annex 2: Survey data; Constructs, questions and scores in percentage

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings. Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=573&layout=html

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||