Learning to Research in Second Life: 3D MUVEs as meta-research fields

Suely Fragoso, Gustavo Fischer, Ana Lucia da Silva, Henrique Freitas, Guilherme Land, Guilherme Loesch, Lucas Trindade, Pauline Mariani, and Yentl Delanhesi

Universidade do Vale do Rio do Sinos, Unisinos, Brazil

ABSTRACT

This paper describes an experiment in teaching ethnographic techniques for applied research in consumer behaviour in on-line communities. The activity took place between March and June of 2007 and involved seven final year undergraduate Communications students. A brief contextualization precedes the report of the experiment, which took place in Second Life and was structured in four stages: (a) analysis of documentation; (b) participative observation; (c) semi-structured questionnaires and (d) triangulation. Evaluation of the process seeks to identify benefits and drawbacks in the use of Multi User Virtual Environments (MUVEs) for teaching in general and for the teaching of research techniques in particular. The conditions of access to Second Life in Brazil are also identified and discussed. Finally some possibilities for future teaching and research undertakings in online environments are presented.

Keywords: Virtual Worlds; Second Life; ethnography; online learning; online research

This article describes the experience of teaching research techniques and strategies using the MUVE Second Life as a field of observation. The activities described were carried out by a group of students in the final year of the Digital Communications line of the Social Communication degree course at the Universidade do Vale do Rio do Sinos, Unisinos, South Brazil, during the first teaching semester of 2007, in the discipline Social Networks and Consumer Behaviour.

INTRODUCTION

The undergraduate courses in Social Communications in Brazil are directed toward the creation of professionals who are:

- Competent in the creation, production, distribution, reception and critical analysis of media, in the professional and social practices related to these actions and their cultural, political and economic insertion;

- Capable of handling the variety and mutability of the social and professional demands of the area, adapting themselves to the complexity and speed of the contemporary world.

- With a broad and integrating vision, one which is both specialized and general at the same time, of their field of work, making possible the understanding of the dynamics of the various modalities of communication and the relationship of these with the social processes from which they derive and in which they occur and;

- Capable of positioning themselves from an ethical-political point of view with regard to the power of communications, the restrictions that can be applied to communications, the social repercussions that can be engendered and with regard to the needs of contemporary society with respect to social communications. (MEC, 2001, p. 16-17).

The courses are structured by specific skill sets, typically Journalism, Pubic Relations, Advertising, Cinema and Radio. In establishing new directives for undergraduate courses in Social Communications in 2001, the Brazilian Ministry of Education opened the possibility of offering courses that fulfill the requirement of other areas of Communication. Responding to this possibility Unisinos, in 2003, planned a course in Digital Communications, which was implemented in 2004.

The Digital Communications undergraduate course is structured as three consecutive years of study, with the first two of these covering 70 disciplines and the production of four digital media products (one for each teaching semester). In the third year, in addition to 8 obligatory activities (6 disciplines and 2 products), the students are provided with a selection of 12 optional disciplines of which they have to study at least 5.

The teaching experiment reported here took place in one of the optional activities provided for the third year of the course, the discipline Consumer Behaviour III – Social Networks and Virtual Communities. This was directed to the study of methods of researching consumer behaviour, particularly ethnographic methods, in online networks. The discipline had seven students registered and took place in twenty weekly encounters of one hour forty-five minutes each with a further ten hours of complementary activity.

PRELIMINARY ACTIVITIES

The discipline was structured in two modules, with the first being dedicated to theoretical approaches and the second to the practice, reporting and discussion of an ethnographic experiment in an online environment. The environment chosen for the experiment was the MUVE Second Life (SL) and the objectives of the observation were (a) the establishment of the indices of recall of (a.1) real brands and (a.2) brands exclusive to SL in two in world locations and (b) the identification of the consumption habits of (b.1) Brazilian and (b.2) other nationality users of SL.

After a general presentation of the proposal for the semester, the first classes were dedicated to the theoretical module. In the first two lectures topics relating to Social networks, from the concept and elements of networks (such as nodes, connections, hubs, clusters, actors, social ties, social capital) to the tools and parameters for the analysis of social networks (degree of connectedness, density, centralization, etc.) and the forms of representation (matrices and graphs). Prior to each class the students received indications of theoretical texts relating to the subjects to be addressed in that class. The presentations were accompanied by syntheses and outlines in HTML created specifically for these classes. These documents were made available to the students immediately after each lecture.

The third, fourth and fifth classes were dedicated to the revision and further study of Consumer Behaviour. This started from the final papers of the students for the prerequisite disciplines Consumer Behaviour I and II, the content of which was revised and deepened in participative classes. All of the classes were supported with projections and the electronic material was distributed to all of the participants.

The sixth class was dedicated to ethnography, starting with the essential concepts and a synthetic overview of the history of ethnographic practice. The possibilities and limits of ethnography were discussed in relation to those of other approaches, above all the quantitative approaches and the focus group techniques. In the seventh encounter techniques and procedures specific to participant observation were presented, with emphasis on the importance of the creation of a good field diary and the need to triangulate this with data and results deriving from other estimates, using different research methods. At the end the ethical questions relating to research involving people, including the legal aspects relevant to field work, were highlighted. The lectures were supported by theoretical texts and accompanied by syntheses and outlines in HTML created specifically for these classes. These electronic documents were made available to the students immediately after each lecture sessions.

The eighth class consisted of the first formal and detailed presentation of the ethnographic exercise to be carried out in the SL environment (brief references to this had been made since the start of the discipline). The stages and objectives of the exercise were agreed and are described in the next section of this text.

The students were requested to create avatars for the research activities and to familiarize themselves with the SL environment. All the students were already familiar with the concept of game avatar, which was defined as the digital element (in the context of this study, a 3D model resembling a human being) which functions as a representation of a human user in the SL universe. All students were also well aware that interacting with other avatars meant interacting with other people. It was stressed that the same moral and ethical values and principles held in offline relations would be required in their interactions within SL. The students who were already users of SL were instructed to create new avatars and to preserve the independence of their new ‘ethnographer’ identity from their pre-existing avatars. This first request for field activity brought a deluge of technical difficulties as some students did not have a home computer compatible with the minimum configuration required for SL or did not have a wideband connection at home. Access to SL on the Unisinos campus, in its turn, was restricted to a single public laboratory and was severely prejudiced by excessive lag, which all indications pointed to being due to the configuration of the internal network of the university. Despite these difficulties all the students managed to create ‘ethnographer’ avatars. The lecturer responsible for the discipline and the course coordinator, who accompanied the activities providing logistic support, also created their avatars. To facilitate the communication between those involved in the exercise a restricted access group was created, entitled Comunicacao Digital - Unisinos, to which the avatars of the lecturer, course coordinator and all of the other participating students were affiliated.

The students were also informed that the observations would take place in two locations, with each student being allocated to one of these locations and that they should not move to the other. Both of the locations were of public access, classified as PG, <no build> and <restrict llpushObject>, and were listed as popular places, containing a similar number of users at various times. In the first location the predominant language would be Brazilian Portuguese and in the second location it would be English (American or British). Two islands with similar profiles and traffic above 90.0001 in April/May 2007 were pre-selected by the lecturer. Given that the exercise required for the discipline did not include any activity that was not compatible with the public nature of the locations chosen, it was considered that obtaining permission from the owners of the locations was unnecessary.

The students were divided between these locations in such a manner that only those with the appropriate proficiency were allocated to observation in the English language environment. A schedule was created that allocated four hours per week in SL for each student, being two sessions of two hours each, for two weeks. Preferably there would be simultaneous observation at both locations, with one student at each. The lecturer would accompany the entry into the field and would be available for clarification of any eventual doubts that might arise. To not interfere directly with the students or their observations, the avatar of the lecturer remained in another location and made contact with the students via in-world Instant Messenger.

The ethnographic apprentices were instructed to not reveal their ‘real’ identities to other avatars at least until the end of the exercise.

The question of revealing the research activity to those being observed had been the subject of an earlier debate, in which the ethical commitment to the community being observed was contrasted to the possibility of the alteration of behaviour due to the awareness of being observed. The need to inform the avatars present, or not, that their conversation was being observed generated interesting debates: some students considered that it was evident that all conversations that occurred in public spaces in SL are public conversations and as such can be freely recorded and reproduced. The majorityof students were shown to have little sensibility of the different legislation with respect to the use of images and opinions expressed in public, but were considerably more apprehensive concerning the cultural, ethical and moral differences inherent to online environments of global reach. As the experiment was pedagogical in nature, without the intention of revealing any information concerning specific users of SL, it was left to the student’s discretion as to whether they would identify themselves or not. There were, nevertheless, strict instructions to the effect that the observations should be carried out discretely, without interference in the routines and rhythms of the native community and to respect the beliefs and values of each of the users of SL.

In the ninth meeting, with the students being aware of the nature of the activity that they would be doing, they were submitted to a theoretical examination. The exam consisted of a single expositive question, which requested a discussion of the limits and potential of the practice of ethnography in online environments.

ETHNOGRAPHIC EXERCISE

The ethnographic exercise was structured in four stages:

- analysis of documentation;

- participative observation;

- semi-structured questionnaires;

- triangulation.

Analysis of Documentation

The analysis of documentation covered three groups of documents, each being analysed by at least two students. These were:

- the official site of SL (http://secondlife.com),

- the site of Grupo Second Life Brasil (in portuguese) (http://www.gruposecondlife.com.br/)

- the site of the company Millions of Us, dedicated to the publicity of real brands and the creation of companies in SL (http://www.millionsofus.com/).

During the tenth session of the discipline the students presented, to their colleagues, a synthesis of the documents analysed, highlighting the aspects they considered to be the most relevant. These presentations were supported with projections and the electronic material was distributed to all of the participants.

The eleventh class examined the reports of the experiences of each student in SL up to that moment (creation of avatars, passage through the tutorial and the first free in-world observation). At this point the students had not been informed of the locations where the experiment was to take place. This first presentation revealed the necessity of a general levelling session and brought to light some of the technical difficulties that were being faced by the students – both accessing from home and from the campus. The material presented by some students allowed for a deeper discussion of the notion of a field diary and of the type of records and notation expected.

So a levelling session was held, to guarantee that everyone knew how to move and the basic forms of communication. This encounter was especially structured as a meeting of all the students and the lecturers and their avatars in both environments, physically present and on-line respectively. The twelfth class consisted of this overlapping of the two environments, during which it was sought to guarantee that the avatars of the students had a more developed appearance than that provided by the default forms of SL, whilst avoiding excesses of accessories or characterization that could upset the users already observed by the lecturer in the environments chosen for the exercise. Any doubts that arose were resolved in such a way that all the students were ready to enter the field individually in the following weeks. In addition to clothes and accessories, each student received an initial value of 10 Linden dollars2.

Participative Observation

The participative observation took place over the next two weeks. The projected two weekly sessions of two hours each per student were held but the schedule was not tightly held whether for technical (availability of the network or equipment) or personal3 reasons.

The classes that were held during the period of the in-world experiment were occupied with the presentation of the notes from the field diaries, which served as the basis for discussion of the ethnographic techniques, in particular the ethical questions and technical problems encountered in the field. The prediction that those ethnographers located on the Portuguese speaking location would encounter Brazilian users and those located at the English speaking location would meet foreigners was not realized, but a reasonable number of different nationalities was encountered by various ethnographers. In the field diary notations and during the discussion of these observations, the comparisons between the behaviour of Brazilians and SL users of other nationalities frequently extrapolated the question of consumer habits. Generally speaking, students considered that Brazilian users were noisier than others. Bad spelling or grammar on the part of Brazilian users was strongly criticised. Several users of different nationalities were reported to give away many details of their offline lives. In some cases, web searches were used to verify such information, often resulting in confirmation.

Figure 1: Examples of field notes from 23 May, 2007. Left, diary of Yentl Delanhesi, on T-Island, starting 22:05h. Right, diary of Ana Lúcia Migowski da Silva (Ilha Brasil), starting 20:00h. A transcription of a conversation is seen in the bottom of the page on the right.

The class in the fifteenth week of the discipline was dedicated to the closure of the discussions on the field diaries and to highlighting the principal aspects observed by each student. It was seen that the involvement of the students with SL during the activities had been sufficiently intense to place critical distance at risk. As a function of this, the initial proposal was re-examined to reiterate the objectives of the observation (verify the indices of recall of brands in the locations and the consumption habits of Brazilians and other nationalities) and the importance of triangulation bringing together various types of data obtained from different techniques, to obtain a better structured diagnosis. At the end of this class the students were presented with the script for the semi-structured interviews, which was to be applied to at least two avatars that each student had met during the participant observation stage. The students were instructed to interview, in preference more experienced friends, and that they had to ask all of the questions in each interview, although not necessarily in the suggested order. They were also instructed to be particularly careful to not induce answers by the formulation of the question. It was also requested that the student recorded the name and the ‘date of birth’ of the avatars interviewed as well as the date and time of the interview. The script for the interview consisted of five questions:

- Do you remember any SL brand that does not exist (or you think does not exist) in real life?

- Have you seen any real life brand in SL?

- Have you bought anything in SL? Do you remember the brand?

- Have you bought anything with a real life brand in SL?

- Have you ever wanted to buy something in real life because you saw it in SL?

In the next class the students presented the results of the semi-structured interviews, which they had carried out during the week. Various students did not find any of the friends that they had made in the previous weeks and ended up having to interview newly made acquaintances.

Figure 2: Transcription of an interview performed by Guilherme Land in T-Online, 13 June, 2007, starting 17:09h. The heading reads: Full Conversation. The name of the avatar interviewed has been pixelated to preserve anonimity.

Triangulation

The following classes were dedicated to the triangulation of the material obtained in the three previous stages, analysis of documentation, participant observation and semi-structured interviews. Finally the presentation and debate of the results of the experience of learning ethnographic research techniques was held. All of the presentations were accompanied by projections and copies of the triangulation reports were presented to the lecturer.

DISCUSSION

Carrying out this experiment in teaching a research technique in SL allowed for the limits and possibilities of the use of MUVEs as educational environments to be verified.

On one hand the environment proved to be inadequate for activities that required the meeting of various avatars at one place, as was the case with the levelling session. When many avatars meet in the same space a very large set of information and communication possibilities compete with the lecturer for the attention of the students, in such a manner that it is very difficult to arrange that everyone concentrates on the matter at hand. The visual emphasis of SL acts as an invitation for the students to play around, which was amplified by the possibility of establishing parallel communication that is imperceptible to the lecturer (via IM). The tendency toward dispersion was only overcome at those times when all of the students were engaged in some specific activity that required the real time visualization of the avatars or objects within SL. This was the case in teaching movement and in the distribution of skins and shapes to normalize the appearance of the avatars.

The technical difficulties encountered in holding this meeting in two environments, both online and offline, cannot be discarded as a potential cause of the dispersion of the students. The slowness of the SL connection on the Unisinos campus made the tasks of loading and rendering the images of the online environment extremely tedious and the slowness became noticeably greater as new avatars were connected from the public laboratory. However the possibility of simultaneously using offline communication was fundamental to the purpose of the levelling session, which was to equalize the knowledge of the whole group.

On the other hand, SL proved to be highly adequate for teaching participant observation. Firstly the size of the MUVE makes customization viable – in this case, the students were sent to different locations according to their proficiency with English and they could select the days and times that were most convenient to them to carry out the exercise, including making changes at the last minute. More interesting was the possibility of varying the requirements and instructions for each student according to their progress in field activities. Additionally different students could observe at the same location, requiring only that they entered on different days or at different times to guarantee encountering different groups of users (there was a zero incidence of two students reporting interaction with the same avatar).

Secondly it was noticeable that the strategy of providing the students with complete freedom of action within SL, but remaining at their disposal to clarify doubts and provide support when required, resulted in a team of apprentice ethnographers that were both seriously engaged with the activity and sufficiently secure to be able to experiment and improvise.

It would have been practically impossible to prevent students from using their ethnographer avatars outside of the times specified for the participant observation. Almost every time that the lecturer accessed SL during the weeks when the exercise was being carried out there was at least one student connected. In the majority of occasions the students were “camping” or dancing to earn money, normal activities for the ‘natives’ of SL. This activity was considered positively, taking into account that one of the greatest challenges to the ethnographer is in ‘adopting’ or involving themselves with the community without, however, losing the capacity to distance themselves that allows for the objectivity (as far as this is possible) of their observations.

The reduction in frequency of consultation of the lecturer over time was noticeable – few students consulted the lecturer after their first field work session and the number of support requests reduced even more dramatically after the first meeting to present and discuss the notes in the field diaries. In this sense the appropriateness of online activity for individualization was very evident, but the advantages of being able to accompany individual entries into SL with real world meetings to share experiences were also very clear.

The discussion of the field diary notes also helped to qualify these notes themselves: in the first week the majority of diaries contained little information, with just one diary meeting the desired profile. Over the next two weeks, without losing the individuality inherent to their different authors, the notes approached the desired level of refinement. The possibility of collecting images or text sequences in real time directly from SL proved to be an excellent support for the field notes. The students themselves quickly realized that it would be insufficient to simply reproduce the conversation sequences by copying and pasting the chat windows and including images obtained using print screen and snapshots. This type of material was widely used by the students to support their observations, but very few times these records were taken at face value.

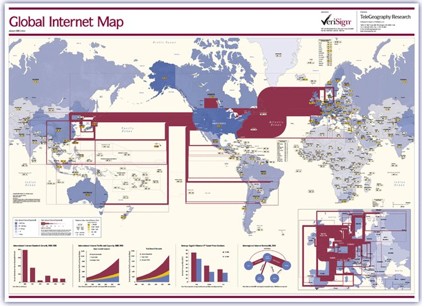

All of the students who informed the other participants that they were in SL to carry out participant observation reported a change in attitude in their interlocutors. In a good number of cases the other users became particularly “collaborative”, with the number of times in which the other refused to continue the interaction or appeared to be intimidated by the observation being few4. Either way, it is certain that knowledge of the nature of the interaction altered the behaviour of those being observed with respect to the students. On the other hand, the absence of explicit objections to participating in the research, be this in the participant observation phase or during the semi-structured interviews, suggests that perhaps online communities consider the presence of researchers less intrusive than offline groups do. This could be as much due to the fact that research in online communities has become frequent and highly publicised as it is due to the technological mediation, which maintains the ethnographer physically separated from the observed parties, providing them with a sense of security. It is interesting to note, however, that this mediation is of the same order and nature as that that separates the users from each other, and thus does not make the experience of the researcher different to the typical interactions of the community. On the contrary, the necessity to use the same devices and technical alphabets brings the experience of the researcher closer to that of the users being observed. In the study reported here, this sharing allowed the overcoming of the notion that the digital divide refers to the difference between having and not having access to digital communications networks and to perceive very directly the nuances that are hidden in this question. Despite it being recognised that the profile of the students of the course that hosted the experiment corresponded to the best provided for layers of the Brazilian population, several of them did not have home equipment sufficiently powerful to run SL and/or did not have a wideband connection at home. Even the best equipped and connected users verified that access to the internet in Brazil is slow in comparison to that in the USA, Europe or Australia. This happens because the available infrastructure for access to the internet in Latin America is much lower than the bandwidth that connects those other regions (Figure 3). The ‘digital divide’ is, therefore, still a great impediment to the popularization of the use of ‘heavy’ online environments such as SL in Latin America (and, as far as can be seen from the map in Figure 4, even more so in Africa).

In addition to the access difficulties, other factors that demotivate potential SL users in Brazil were noticed during the participant observation. Practically all of the field diaries noted that presence of novices who were trying SL for the first time. The subject of conversation amongst the newcomers were how to make money, how to obtain sexual favours, or both, which is consistent with the description of SL given by the Brazilian media. The majority of these newcomers must have been disappointed by the environment as, despite the sensationalist reports, the moral standards that dominate in SL appear to be very similar to those offline. Modesty with respect to avatars, for example, is as strong as the erotic appeal: despite there being various locations intended for the staging of sexual acts, the presence of a naked avatar in a public space tends to result in revulsion and repudiation even if the avatar is not doing anything inappropriate. Either way, what can be affirmed on the basis of the experience of the group in SL is that the type of portrait that the major Brazilian media have constructed of SL has really led many people to try the system, but it is doubtful that it has contributed much to the number of regular users.

Figure 3: International Internet backbone architecture scaled by aggregate capacity. Reproduced from Telegeography, 2006.

As well as it being probable that a great number of newcomers abandon the system after a few first connections5, the online population varies in the sense that there is a variation in the access times and locations frequented in SL. As a result of this, a large number of students did not manage to relocate the avatars that had become friends during the participant observation, having to resort to holding the semi-structured interviews with users they were interacting with for the first time. This alteration to the projected flow of the research was providential for teaching in the sense that it gave, once more, the perception that reality does not fit to the models predicted in the research and engendered discussion on the means to cope with the difficulties found in the field and how to adapt the techniques to the observation conditions whilst minimizing the prejudice to the objectives of the research. In this case, the option to interview avatars with which no previous familiarity had been established appeared not to disturb the results, as there was no noticeable difference between the replies of the previously known interviewees and those with whom the students were interacting for the first time.

In general, the most positive responses with respect to the recall of brands came from the older avatars. With respect to the consumption habits there was little difference between the replies of the most experienced avatars and the newcomers, with the great majority of respondents reporting that they did not obtain virtual objects of higher values, only being willing to pay more than 1 Linden for pieces of exceptional beauty or quality.

NEXT DEVELOPMENTS

The experience of carrying out part of the activities of an undergraduate discipline in a MUVE was certainly interesting. SL demonstrated great possibilities in terms of the customization of activities, allowing for each profile of student to be catered for specifically.

The meeting of various avatars at one location in a graphically rich environment with the possibilities of action provided by SL, on the other hand, proved to be a problem. Additionally the conversation through the open chat window is not favourable to holding classes in SL, as the comments mingle and it is difficult to follow the dialogues. The public conversation also suffers from competition with the parallel interactions, via IM, that remain invisible to the lecturer. The availability of voice can make the system more effective for communication to groups of people, but against this, the possibilities of manipulating the sound adds to that of playing with the images to invite more still the playful use of the environment.

It is, however, necessary to question the purpose of bringing all the avatars together at one location in SL. Unless there is the intention to create or modify objects in real time using a process that is visible to all, or that there is some specific demand that the avatars be visible to each other, the assembly of all the avatars and the lecturer in a single location in the MUVE seems to be simply one more case of the acritical adoption of offline habits in an online environment. After all, contrary to what happens in the physical classroom, the appearance of the avatar does not offer any information whatsoever concerning the enthusiasm or attention of the student on the other side of the screen.

With respect to the experiment reported here, there are signs that the students took more seriously and engaged more intensely with the activities that did not plan the sharing of the same space in SL, in such a way that the individual communication through IM or through the Comunicacao Digital – Unisinos Group, additionally to facilitating the process, appeared to provide incentive and autonomy to the students.

Finally the experience emphasised the perception that the digital divide should be understood with a refinement that is not covered by the division between those that have and those that do not have access to the Internet. Despite the nature of MUVEs permitting the holding of classes with students located in different regions of the planet, the great variation in the availability of the infrastructure places the possibility of transcontinental lessons in check. The linguistic and cultural differences also act as complications for the realization of cross-cultural classes: inclusive of one that has been ever-present throughout the construction of this report; the differences in the classroom environment in the USA and Europe and the classes held in Brazil. The variation in levels of formality, in the expectations of the lecturers and students, in the dynamics and even in the duration of classes between the different countries could compromise the understanding of the reach and nature of the experiment reported here. For this reason the idea of using SL to promote meeting between students of courses with similar profiles based in different countries appears to be particularly promising, in the sense of promoting a better understanding of the realities of education in different cultures.

ENDNOTES

1. Since 2006, traffic in Second Life has been calculated by a function that includes the number of avatars who have been in that location and the amount of time they spent there (Second Life Forums, 2007).

2. The Linden dollar is the in-world currency. It can be used, for example, to buy goods and to obtain the right to engage in certain in-world games.

3. It has to be noted that the course was timetabled for the morning and the majority of Brazilian students work in the afternoons or even at night, which required that the hours had to be made flexible to meet the availability of the students.

4. It is not possible to affirm that that any user interrupted the interaction due to feeling uncomfortable with the research given that the proportion of users that abruptly interrupted their interaction with the apprentice ethnographers was similar regardless of whether they revealed that they were involved in a participant observation exercise or not.

5. The unavailability of data concerning inactive or deleted accounts is one of the constant criticisms made to the statistics for Second Life published by Linden Labs.

REFERENCES

Author 1, Author 2; M. B. Bohn and H. Reis, 2003, Projeto Curricular do Curso de Comunicação Social - Habilitação: Comunicação Digital Nível: graduação. Presented and approved by the Conselho Universitário of the Universidade do Vale do Rio do Sinos, Unisinos, Resolução CONSUN 015/2003 de 08 de outubro de 2003. Unpublished.Grupo Second Life Brasil, 2007. Grupo Second Life – Brasil. Retrieved 15 August 2007 from http://www.gruposecondlife.com.br/Linden Research, Inc., 2007. Second Life: your world, your imagination. Retrieved 15 August 2007 from http://secondlife.com

MEC, 2001. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais dos cursos de Filosofia, História, Geografia, Serviço Social, Comunicação Social, Ciências Sociais, Letras, Biblioteconomia, Arquivologia e Museologia. Diário Oficial da União, 9/7/2001, Seção 1e, p. 50. Retrieved 9 August 2007 from http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/ces492_01.pdf

Millions of Us, 2007. Millions of Us. Real Worlds. Real Brands. Retrieved 15 August 2007 from http://www.millionsofus.com/

Second Life Forums, 2007. Traffic ??? Thread initiated in 08-20-2007, 03:16 PM. Online from http://forums.secondlife.com/showthread.php?t=205444 [restricted access] [20/03/2008]

Telegeography, 2006. Global Internet Map. Retrieved 15 August 2007 from http://www.telegeography.com/products/map_internet/index.php

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings. Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=467&layout=html

|