Using ICTs in Teaching and Learning: Reflections on Professional Development

of Academic Staff

Markus Mostert and Lynn Quinn

Rhodes University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Focussing on professional development of academic staff as higher

education practitioners, this paper reports on the relationship between ICTs

and teaching and learning in higher education, and on the way that that relationship

plays out in a formal staff development course offered at Rhodes University,

South Africa. The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) framework

developed by Mishra and Koehler (2006) is used as a theoretical lens for demonstrating

the undesirability of an unnatural separation of ICTs from teaching and learning

in dominant discourses within institutional and national environments. The

paper concludes by highlighting some implications of the TPCK framework for

staff developers and curriculum design in higher education.

Key words: information and communications technology (ICT);

learning technologies; professional development; academic development; educational

development; curriculum design.

INTRODUCTION

Internationally the way in which higher education (HE) is conceptualised

is changing. Globalisation, massification, shrinking resources, the proliferation

of information and communication technologies (ICTs), increased demands for

quality assurance and greater public accountability, and increasing competition

among higher education institutions have all contributed towards changing

the traditional role of academics. Academics now operate in what Barnett (2000)

terms “a world of supercomplexity”, where the very frameworks

on which their professions are based are continuously in a state of flux.

Technological and economic changes, for example, have resulted in a reorganisation

of time and space (Giddens 1984, cited in Unwin 2007). Furthermore, the supercomplexity

and uncertainty of the postmodern world have caused people to be more reflexive,

which, in turn, has led to a heightened sense of ontological insecurity for

academics (ibid).

This changing context of higher education (HE) both internationally

and in South Africa presents new challenges for lecturers. In particular,

the expansion of the application of technology in teaching and learning has

been one of the most ubiquitous major recent changes in higher education (D’Andrea

and Gosling 2005). On the one hand the use of ICTs is presented as a solution

to many of the teaching and learning challenges brought about by the new HE

landscape, while, on the other hand, starting to use ICTs in their teaching

and their students’ learning often represents an almost insurmountable

obstacle to lecturers.

Some of the ways in which higher education institutions have

responded to the challenge of implementing ICTs in teaching and learning include

developing coherent institutional strategies to change (see for example, McNaught

and Kennedy, 2000 and Salmon, 2005), focussing on the impact of learning technologies

(Beetham et al., 2001, Timmis, 2003 in Conole, White and Oliver, 2007) and

the offering of models for representing and understanding organisational contexts

and change management (Morgan, 1986 and Mumford, 2003 in Conole, White and

Oliver, 2007).

Yet another strategy employed by higher education institutions

in response to such challenges and which this study reports on, focuses on

support and staff development issues (Smith and Oliver, 2000; Oliver and Dempster,

2003 in Conole, White and Oliver, 2007), placing greater emphasis on the professionalisation

of academic staff as teachers and assessors. Staff development units are tasked

with contributing to the professional development of academic staff in HE

through professional development workshops and courses leading to formal qualifications.

Through these initiatives Academic Development (AD) staff need to find ways

of not only helping academics cope with these changes, but also of assisting

them in developing appropriate strategies for preparing their students to

operate successfully in a world of “supercomplexity”.

With regard to the use of ICTs in teaching and learning, however,

a major problem is that staff developers themselves are often ill-equipped

for using ICTs in their own teaching and courses, let alone for assisting

academic staff to follow suit.

In response to these challenges, Unwin (2007) proposes a model

of professional development that entails the establishment of professional

learning communities as a way to counteract the sense of ontological insecurity.

Following from the “communities of practice” concept developed

by Lave and Wenger (1991) and Wenger (1998), such learning communities are

important as they could contribute towards lecturers reconceptualising their

professional identities. For Knight and Trowler a community of practice is

“a closely interacting group of practitioners within which contextualized,

situated learning is always happening and is legitimized” (2001, 9).

Such communities “have the potential to encourage teamwork, democratic

discourse, creativity and trust” (Unwin 2007, 298). Also, within a learning

community people bring along different resources and expertise which they

can share with members of the group. Wenger (1998, 85) argues that

These professional communities have allowed a sense of belonging

and confidence in shared decision-making when (often) external factors seemed

to be working against us … (in Unwin 2007, 296).

In an environment which is not always supportive of change,

Academic Development (AD) staff are challenged to design workable strategies

in formal professional development courses for promoting effective practice

in teaching with technology. Investigating the relationship between ICTs and

teaching and learning in higher education, this paper uses the Technological

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) framework developed by Mishra and Koehler

(2006) as a theoretical lens for reporting on the practice in a staff development

course for academics at Rhodes University, South Africa.

ICTs AND HIGHER EDUCATION

Many have regarded ICTs as the solution to a range of educational

problems. In South Africa, much of the discourse on using ICTs in HE teaching

and learning, however, seems to focus on access to technology; that is, on

the availability of computers, the Internet and bandwidth rather than on the

way ICTs are being used in support of teaching and learning. In many contexts

this focus on access has resulted in pedagogically poor applications of technology

where ICTs are only used in transmission modes of teaching and learning. Following

some spectacular failings of eLearning projects globally, (see, for example,

Latchem, 2005) there now seems to be a growing concern about the application

of those technologies in teaching and learning to investigate how they can

and are being used to support teaching and learning (see for example, Czerniewicz

and Brown, 2006).

In addition, there has been a growing recognition that technology

used in the absence of a sound theoretical framework or pedagogy is generally

not very effective in reaching programme goals. Laurillard (2002); Mishra

and Koehler (2006) and Unwin (2007), for example, have cautioned against the

use of ICTs without a conceptual framework or without a clear understanding

of why and how the ICT will contribute to students’ learning. These

insights have led some higher education institutions (HEIs) to realise that

pedagogically sound integration of ICTs in lecturers’ teaching requires

more than technical support; it also needs professional development for lecturers

to use ICTs in their teaching and learning.

There seems to be a wide variation in how HE practitioners conceptualise

the integration of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in teaching

and learning. This implies a question concerning our understanding of learning

with ICTs and the implications for the professional development of academic

staff.

Discourses on ICTs in HE separate ICTs from teaching

and learning

Following Shephard (2004), we use the concept of ICTs in teaching

and learning to broadly include computer-based and online tools and resources

used to support student learning, but we also focus on the interactive use

of those tools to facilitate interpersonal communication and collaboration.

At Rhodes University, however, many of the discourses on the role of ICTs

in teaching and learning seem to conceptualise the use of computers in isolation

from lecturers’ teaching practice. Users of one such dominant discourse,

for example, believe that the use of ICTs only add value to those students

who are under-prepared for higher education studies. Such students should

therefore be sent to a computer laboratory to work through a computer-based

tutorial or other courseware product on a particular topic. This thinking

is in line with a model of computer-based education that emphasises learning

as the transmission of content over the construction of knowledge and seems

to be loosely based on behaviourist theories of learning, even though their

designers might profess constructivism as the underlying theory of learning

(Thorpe, 2002). In this model, students “learn” or supposedly

“construct their own knowledge” by working, often sequentially,

through courseware lessons such as computer-based “tutorials”,

drill and practice programs, simulations, tests and games (Alessi and Trollip,

1991).

Given the way in which ICTs are dealt with in isolation from

teaching and learning in official documentation pertaining to teaching and

learning, this separation of ICT-use from other teaching and learning endeavours

in South African Higher Education comes as no surprise. The same division

is, for example, reflected in the Higher Education Quality Committee’s

(HEQC) Improving Teaching and Learning (ITL) Resources (2005). Developed during

2003 in a series of workshops the ITL Resources was a collaborative project

between the HEQC and academics in private and public higher education institutions

in South Africa and other countries. Aimed at quality promotion and capacity

development these resources contain suggested good practice descriptors that

are consequently used as the basis for the institutional audits conducted

at various South African higher education institutions.

With regard to the use of ICTs in teaching and learning, the

ITL Resources contain the Unit Standards for a Web-based Learning elective

module, which forms part of a postgraduate qualification for higher education

practitioners, (the Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education and Training

or PGCHET), aimed at providing professional development and recognition for

HET practitioners. However, apart from this elective, all of the references

to computer(s), IT (information technology), technology and the Web relate

to access and the provision of resources and services. Where the use of ICTs

is somehow connected to learning in these ITL Resources, references to ICTs

are used exclusively in relation to the development of computer literacy skills

for both students (2005, 112) and staff (2005, 141), despite a recognition,

in these very resources, that

… technology has revolutionised teaching and learning;

and academic staff members now face the challenge of introducing effective

ways of engaging technology for learning (HEQC 2005, 140).

Furthermore, in the unit standards for the PGCHET itself, the

use of ICTs in teaching and learning is dealt with in isolation from other

core modules such as curriculum development, assessment, evaluation and learning

design. While the unit standard for the elective module mentioned above, Design

and develop web-based learning, specifically focuses on the use of ICTs in

teaching and learning, none of the other seven compulsory core unit standards

or four elective unit standards addresses the issue of using ICTs in support

of teaching and learning. We believe that this separation of the use of technology

from other teaching and learning topics severely limits the potential of ICTs

to enhance teaching and learning.

Fortunately, due to the widespread use of the Web and the increasing

pervasiveness of ICTs as experienced by university educators and students,

the practice of isolating educational technologies is increasingly being challenged

in favour of practices based on social constructivist learning theories that,

for example, emphasise interpersonal interactivity over interaction between

a student and a courseware program. Consequently, computers are assuming a

more central role in mainstream teaching and learning.

This shifts the location of learning beyond the confined spaces

of “the lecture” and student computer laboratories with limited

“opening hours” towards learning anytime and anywhere, with profound

implications for the everyday practices of teaching, learning, research, administration

and recreation.

Since “there is no single technological solution that

applies for every teacher, every course, or every view of teaching”

(Mishra and Koehler 2006, 1029), the appropriate and pedagogically accountable

integration of ICTs into teaching and learning, however, presents many challenges

which have to be addressed in professional development courses.

Implications for professional development

Due to the relative newness of the field as well as the increasing

pace of technological change, much of the work being done in relation to the

use of ICTs in teaching and learning can be described as exploratory and thus

is often implemented in the absence of well developed theoretical frameworks

(Unwin, 2007). Practice that develops slowly and theory hardly at all (Laurillard,

2002) severely limits the potential of ICTs to enhance teaching and learning.

It is therefore unsurprising that ongoing debate seems to characterise discussions

about the most appropriate way of supporting academic staff in using ICTs

in their teaching and in their students’ learning. Shephard (2004, 67),

for example, distinguishes between the provision of technological support

to describe an orientation of “let us help you to develop and use these

learning resources” and professional development to signify the scaffolding

provided to lecturers to help them develop the theoretical understandings

and skills that they will need “to find, develop, and use these learning

resources” in ways which contribute to the kind of learning that is

valued in higher education.These different orientations to assisting academic

staff to integrate ICTs in their teaching and learning have very specific

implications for educational technologists and academic development practitioners

alike.

With regard to the support model, the term “instructional

designer” is often used to describe the role of educational technologists.

In supporting staff (“let us help you to develop and use these learning

resources”), both an instructional designer and a lecturer (as content

expert) would often be part of a courseware development team which might include

one or more of the following: a project manager, a graphics or web designer,

a programmer, a web developer, etc. Instructional designers would therefore

engage in specific projects (e.g. developing a piece of courseware), with

target and sign-off dates, often following well-established software development

models such as the modified ADDIE model as described by Kruse and Keil (2000).

In a professional development context, however, educational

technologists increasingly fulfil the role of “curriculum designer”

alongside one or more academic staff members in a curriculum development team

(Littlejohn and Peacock, 2003). In this context, educational technologists

are more likely to play the role of “curriculum designers” (rather

than that of instructional designers), resembling the function of academic

development practitioners more closely. Here emphasis moves away from specific

ICT-based interventions (for example as in the case of developing a piece

of courseware) to a series of consultations over a longer period of time,

in a whole module or course that is presented over anything from a few weeks

to an entire academic year. Lecturers starting to use a learning management

system usually make small incremental changes to their courses and teaching

as they adopt various tools or features of a learning management system (LMS)

over a period of time. In this process they would be assisted by an educational

technologist (acting as a “curriculum designer”) who would work

alongside them to negotiate the pedagogical implications of various options

of using ICTs (Oliver, 2002).

The support model described above might have a more direct and

radical impact on the teaching and learning in a particular course. However,

this is also exactly the reason why this approach attracts fewer academics:

… the historic constancy of lecturing methods on campus

may make it hard for faculty to imagine strategies that take them outside

an intuitive core of shared assumptions and beliefs about teaching methods

(Daniel 1996, 137).

The combination of increased use of LMSs in higher education,

inflexible course structures, time tables and the dominance of the “performance”

model of teaching (Morrow, 2007) therefore seem to have shifted the role of

educational technologist from “instructional designer” to “curriculum

designer”.

After outlining the context and some of the challenges involved

in the integration of ICTs within a Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education

(PGDHE) course we will use Mishra and Koehler’s (2006) Technological

Pedagogical Content Knowledge Model as a lens through which to view our own

practice.

ICTs in a Professional Development Course

Since 2000 Academic Development (AD) staff members at Rhodes

University in South Africa have offered a Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education

(PGDHE) aimed at professionalising the practice of academic staff in the Institution.

Although the curriculum for the PGDHE was developed by a team of AD practitioners,

the team did not initially include an educational technologist. At the time

the application of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to teaching

and learning was addressed in the PGDHE through stand-alone presentations

by an educational technologist. These stand-alone presentations did however

not seem to lead to either successful learning about ICTs in teaching and

learning, or to significant implementation of ICTs in participants’

teaching and courses. According to Mishra and Koehler (2006) this de-contextualised

practice is indicative of the knowledge structures that underlie much of the

current discourse on educational technology that separates technology from

pedagogy and content.

The introduction of a learning management system into the PGDHE

in 2005 resulted in closer collaboration between the AD practitioners teaching

on the programme and the educational technologist in the department. This

has led to the formation of a “professional learning community”

(Unwin 2007, 295) comprising the AD staff and the educational technologist,

which has enabled an “integrated pedagogic approach to ICTs”.

Since ICTs are now used to support participants’ learning in the PGDHE,

the use of ICTs to enhance teaching and learning in Higher Education is modelled

for participants to use in their own teaching.

The Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education (PGDHE)

The curriculum for the PGDHE offered at Rhodes University is based on the

South African unit standards for the PGDHET, the competency-based national

qualification for lecturers in HE mentioned earlier. Since the curriculum

development team adapted the unit standards into a modular format, the curriculum

for the PGDHE displays a higher level of theoretical coherence than is usually

associated with unit standard-based programmes. Based on the curriculum development

team’s shared theoretical and philosophical beliefs about what constitutes

an appropriate approach to the development of academic staff in higher education,

the practice-based, two-year course was designed to meet the specific needs

of lecturers within the context of their disciplines, the university, and

the higher education context, nationally and internationally. The stated purpose

of the course is to encourage the professional development of lecturers by

assisting them to enhance their ability to facilitate, manage, and assess

their students’ learning, to evaluate their own practice effectively,

to develop their knowledge of higher education as a field of study, and to

provide professional accreditation (Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education

Course Guide, 2006). The programme is offered in the form of four core modules

(Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Curriculum Development; Assessment

and Moderation of Student Learning and Evaluation of Teaching and Courses)

and one elective module.

Despite the positive evaluations on the programme as a whole

(see Quinn, 2003; 2006), the curriculum development team has always felt that

the add-on workshops on technology, although offered as part of specific modules,

were not successfully encouraging participants to use technology to enhance

their teaching and their students’ learning. This perception was borne

out by our analysis of participants’ teaching portfolios, the primary

method of summative assessment in the programme, which contained little evidence

of their using ICTs in their teaching, and from feedback we elicited from

them.

Learning about ICTs in the PGDHE

At our institution the close relationship between ICTs and teaching

and learning has been recognised in that the position of the educational technologist

is based in the unit that is mandated to develop teaching and learning, rather

than in, for example, the division that is tasked to provide ICT infrastructure

and services to the institution. While the academic development staff members

have always recognised the importance of integrating ICTs into teaching and

learning, we were less certain about the most appropriate way in which it

could be integrated. Consequently, ICTs in teaching and learning were initially

treated as an “add-on” rather than central to teaching and learning.

This was also evident in the development of the Postgraduate Diploma in Higher

Education (PGDHE). Based on national unit standards this programme made provision

for the “teaching” of ICTs in teaching and learning through an

elective module worth 10 credits (initially called “Design and develop

web-based learning”) and one 90-minute session in each of the “Learning

and Teaching in Higher Education” and “Assessment and Moderation

of Student Learning” modules. While the elective, now called “ICTs

in Teaching and Learning”, provided PGDHE participants with the space

to investigate and report on an ICT-related intervention, take-up of this

elective was very low with only approximately 17% of participants taking this

elective over a 5-year period.

Following several years of experimenting with various web-based

learning management systems (LMSs), the institution adopted Moodle in 2004.

While the LMS initially had very little impact on the way that the PGDHE was

taught, the facilitators of the programme started using the LMS as a repository

for resources (in 2005), but later also more interactively by requiring PGDHE

participants to reflect on their learning in online journals (in 2006) and

in participating in online discussion forums (in 2007). The primary aim of

integrating ICTs into the PGDHE was to expose participants to the potential

of ICTs to enhance their teaching and their students’ learning by modelling

the use of ICTs. This is particularly significant as very few, if any, of

the PGDHE participants had any previous experience of being taught using ICTs.

While we do not claim that this integrated model of imbedding ICTs into the

curriculum was solely responsible for the increasing uptake of the LMS amongst

PGDHE participants for their own courses, we will assert that it is a more

pedagogically sound approach than the earlier practice of de-contextualised,

add-on presentations in two of the modules as described above.

TECHNOLOGICAL PEDAGOGICAL CONTENT KNOWLEDGE AS THEORETICAL

LENS

The need to have conceptual lenses through which to explore

research data has been thoroughly argued (see for example, Mishra and Koehler,

2006 and Oliver, 2003). Such theoretical lenses allow researchers (and practitioners)

to make inferences about the world. May goes so far as to claim that the findings

of social researchers are meaningless unless they are situated in a theoretical

framework which must be made explicit: the “facts do not speak for themselves”

(2001, 30). Furthermore he argues that social theory and concepts are necessary

both for interpreting empirical data, but also as a basis for critical reflection

on the research process, and social life and social systems in general. The

main aim of our research was to use the available theory to help us begin

to uncover the mechanisms and processes at work in our context.

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge

There seems to be emerging consensus that the integration of

ICTs into teaching and learning requires balancing different sets of knowledge

and skills. Inglis, Ling and Joosten (1999, in Shephard, 2004), for example,

identify three zones of expertise: expertise in information technologies,

expertise in instructional design and expertise in a subject area. Based on

Shulman’s (1986) notion of pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) Mishra

and Koehler (2006) developed a theoretical framework that not only corresponds

closely with the zones of expertise identified by Inglis et al., but also

identifies four additional sets of teacher knowledge bases by focussing on

the areas of overlap between each pair in this triad, as well as the interplay

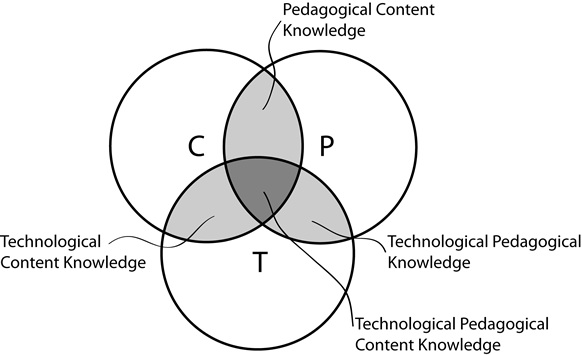

of all of three of these primary knowledge bases (See Figure 1). For Mishra

and Koehler,

TPCK represents a class of knowledge that is central to

teachers’ work with technology. This knowledge would not typically be

held by technologically proficient subject matter experts, or by technologist

who know a little of the subject or of pedagogy, or by teachers who know little

of that subject or about technology (ibid, 1029).

Claiming that this framework enables a deeper understanding

of a range of contextually bound and complex relationships, Mishra and Koehler

(2006) argue that

a conceptually based theoretical framework about the relationship

between technology and teaching can transform the conceptualisation and the

practice of teacher education, teacher training, and teachers’ professional

development (ibid, 1019).

Figure 1. The Technological Pedagogical Content Framework (Mishra

and Koehler 2006, 1025)

As explained above, much of the earlier theorising about the

use of technology in education involved viewing technology as being separate

from both content and pedagogy. A number of scholars have pointed to the failings

of traditional add-on methods for teaching the use of technology. Mishra and

Koehler, for example, regard these methods as “ill suited to produce

the ‘deep understanding’ that can assist teachers in becoming

intelligent users of technology for pedagogy …” (ibid,

1032) and suggest that it is necessary to integrate the use of educational

technology with sound pedagogy and that doing this requires the development

of “a complex situated form of knowledge that [they] call Technological

Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK)” (ibid, p. 1017). TPCK

emphasises “the connections, interactions, affordances, and constraints

between and among content, pedagogy, and technology” (ibid,

1025).

In practical terms, apart from looking at the three types of

knowledge in isolation, Mishra and Koehler suggest that it is necessary to

examine them in pairs: pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), technological

content knowledge (TCK), technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) and the

three combined as technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK). Substantially

expanded from Shulman’s initial three categories, this model is useful

for helping researchers to decide which research questions they need to ask

and what data it is necessary to collect. As will be described below, we were

interested in determining whether the participants on a professional development

course had developed TPCK. The following elements and relationships were considered:

Content knowledge. In the context of a professional

development course which is made up of lecturers from a range of disciplines

it is safe to assume that they have or are able to acquire the disciplinary

knowledge they require for teaching. In such a cross-disciplinary course for

lecturers it is therefore neither practical nor necessary to teach “content

knowledge”. Participants should however be encouraged to critically

examine their disciplines; to think about issues such as what counts as knowledge

in their disciplinary areas, and so on (see for example Quinn and Vorster,

2004).

Pedagogical knowledge. Mishra and Koehler define pedagogical

knowledge as “deep knowledge about the processes and practices or methods

of teaching and learning and how it encompasses, among other things, overall

educational purposes, values and aims” (ibid, 1026). This kind of knowledge

is the focus of a professional development course for lecturers in higher

education. In addition, another purpose of such a programme is to encourage

participants not just to develop their disciplinary identities (e.g. lawyer,

historian, geologist), but also to develop their identities as teachers in

HE. For this to happen, participants need to be exposed to current theories

of teaching and learning generally and those applicable specifically to HE

contexts.

Pedagogical content knowledge is knowledge linked to

the teaching of a specific discipline. PCK explores, for example, the difference

between teaching history and teaching chemistry or drama. It requires knowledge

of which curricula and teaching and assessment methods are most likely to

achieve the learning outcomes of specific disciplines and courses.

According to Mishra and Koehler, PCK “is concerned with

the representation and formulation of concepts, pedagogical techniques, knowledge

of what makes concepts difficult or easy to learn, knowledge of students’

prior knowledge, and theories of epistemology” (ibid, 1027). Pedagogical

content knowledge also includes the ability for disciplinary experts to make

explicit the academic literacies of their disciplines (Boughey, 2002) to enable

students to understand not only what counts as knowledge in their disciplines

but also how to express that knowledge. In the context of a cross-disciplinary

professional development course such as the PGDHE, much of this cannot be

explicitly taught but participants can be asked critical questions which encourage

them to transfer generic pedagogical knowledge and apply it to the teaching

of their specific disciplines.

Technology knowledge. We would like to believe that

lecturers in higher education should come with some basic level of computer

literacy skills. They should, for example, be able to work with computers,

networks, the Internet and understand operating systems, computer filing systems

and so on, in the same way that they are able to work with books, pens, and

overhead projectors, for example. We are aware, however, that this picture

does not reflect the current reality at Rhodes University. Since all seven

parts of TPCK are necessarily integrated and should not be viewed in isolation,

participants’ potential lack of basic computer literacy skills might

jeopardise their development of TPCK. Since we do not see the development

of basic computer literacy skills as core to our function, these literacies

are being addressed by the Human Resources Division. Within the PGDHE course,

such skills are therefore only addressed on an ad-hoc, just-in-time basis

when required.

Technological content knowledge is “knowledge

about the manner in which technology and content are reciprocally related”

(ibid, 1028). Again, in the model which we propose for professional development,

TCK is not explicitly taught, but it is modelled through the use of technologies

to teach the programme. Due to the practice-based nature of the PDGHE, participants

are encouraged to reflect on how technology is used and to think about how

they could apply it in their contexts.

Technological pedagogical knowledge is made up of generic

knowledge regarding how technology can be used for general pedagogic aims.

While TPK is not directly addressed in the PGDHE, the educational technologist

offers hands-on workshops which focus on the potential of technology to support

teaching and learning in general and aim to develop participants’ TPK.

Technological pedagogical content knowledge emerges

from and goes beyond the three basic components of content, pedagogy, and

technology. For Mishra and Koehler,

quality teaching requires developing a nuanced understanding

of the complex relationships between technology, content and pedagogy, and

using this understanding to develop appropriate context-specific strategies

and representations (ibid, 1029).

In their framework, and in the way in we theorise our practice,

separating the components is only for the purposes of analysis. In reality

all seven are necessarily integrated and should not be viewed in isolation

from one another; they exist in dynamic tension. It is obvious then that content

neutral, add-on generic courses or workshops to train lecturers to use ICTs

in teaching and learning, while they have a valid place and purpose, are unlikely

to lead to integrated knowledge which will enable lecturers to take full advantage

of the potential of educational technologies to enhance their teaching. TPCK

is more likely to help academic staff to develop the kinds of curricula, teaching

and assessment methodologies that will ensure that their students engage in

the kind of learning appropriate for their context.

Further Reflections on our Programme

Mishra and Koehler found that the TPCK framework helped them

to articulate “a clear approach to teaching (learning technology by

design), but also served as an analytical lens for studying the development

of teacher knowledge about educational technology” (1041).

Their framework has enhanced our understanding of the practices

which we are implementing intuitively. Using the framework enabled us to analyse

evaluation data and to critically reflect on the relationship between content,

pedagogy and technology and on how we were developing the range of different

knowledges in our programme. It enabled the “development of deeper understandings

of the complex web of relationships between content, pedagogy, and technology,

and the contexts in which they function” (ibid, 1043). Assisting us

in building metacognitive understandings of our practices, the TPCK model

will in future enable us to consciously integrate the development of TPCK

in a more deliberate and theorised way.

Our analysis of course evaluations and our own critical reflections

show that we as educational developers and other lecturers as participants

on the PGDHE, have made shifts towards developing TPCK, that is, a more nuanced

understanding of the relationships between the three types of knowledge and

how to develop TPCK in a way which is commensurate with the aims, purposes,

underpinning philosophy and outcomes of the PGDHE. Lecturers who attended

our professional development programme in 2007 are beginning to acquire the

appropriate knowledge which will enable them to use ICTs in their own teaching

in ways which will lead to the kind of learning valued in higher education.

It is our contention that the formation of a curriculum development

team which included an educational technologist and our using of ICTs to teach

the PGDHE enabled us to powerfully model ways of integrating ICTs into teaching.

Participants were thus able to experience firsthand the potential of using

ICTS in this way for their own learning in the PGDHE. Most of the participants

believe that their learning was significantly enhanced by having access to

a LMS. Pointing to some specific features of the LMS, other participants described

their experiences in the following ways:

The journals have been a very useful way to record my thoughts

about the learning tasks … it’s been a very good way of receiving

comments back from my course facilitator. I think this system works very well,

and it’s a very convenient way of exchanging information, and then storing

it in one place. … The journals are also a ‘safe’ space

to record your thoughts when you’re not necessarily on top of the material

yet – it is then very useful for reflective purposes to go back later

and see how your own views and understandings have changed.

I found the … journal entries to show progression

in my thinking and allow me to ‘build’ a piece of work. Forum

discussions have been really great – as we can easily share our thoughts

at a convenient time and refer back to what has been said.

Some of the feedback from course participants provides evidence

that they began to acquire the appropriate TPCK to use ICTs in the design

of their own courses and modules:

... using Moodle in the course has made me aware of its

potential in my teaching – this has been the best way of demonstrating

it to us.

I have become so aware of it [need to integrate ICTs in teaching and learning]

that I have made it my elective to investigate the potential to use it at

my college.

… how I am currently using Moodle is that it is a resource site at the

moment, but it is an interactive resource site … I’ve sectioned

off stuff so as to lead people gently into what its all about and then added

the use of the calendar tool, where I keep updates on all sorts of useful

information …it’s really cool. I’ll be ready next year.

CONCLUSION

If, according to Mishra and Koehler (2006) educators have to

develop or maintain these seven sets of knowledge bases, what are the implications

for academic development staff who are tasked with the professional development

of these educators? Which sets of knowledge bases should they possess or develop

for themselves?

Implication for staff developers

As discussed earlier, due to the specificity of content knowledge

in various disciplinary contexts, it is neither feasible nor desirable for

academic development staff to be responsible for lecturers acquiring any of

the Content Knowledge, Technological Content Knowledge, Pedagogical Content

Knowledge or Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge for any disciplines

other than in the disciplinary area of Education and related fields (e.g.

Psychology, Adult Education, etc.), which is already represented as Pedagogical

Knowledge in the TPCK model. While educational developers would normally,

by virtue of the field they are working in, have already acquired Pedagogical

Knowledge, the possibility of them having developed Technological Knowledge

and Technological Pedagogical Knowledge is rather slim. This is often because

they too, have not experienced being taught with digital technologies, but

primarily because the structures in which educational technology operate frequently

perpetuate the undesirable split between the development of teaching and learning

on the one hand and the use of ICTs in teaching and learning on the other.

Assuming that staff developers have already developed their

Pedagogical Knowledge, they would be required also to develop their Technological

Knowledge as well as their Technological Pedagogical Knowledge so as to enable

them to become comfortable in advising lecturers on the potential role of

ICTs in their teaching and curricula and thus maintaining their professional

status and credibility as staff developers. Educational Technology will consequently

have to be perceived as less focused on technology and more orientated towards

effective teaching and learning. Working in teams which include an educational

technologist seems to be one way in which academic staff developers can begin

to gain the other types of knowledge that will enable them to help their “students”

develop TPCK.

Implications for curriculum development

In line with the ideas of many academic development practitioners

(see, for example, Toohey, 1999; Mishra and Koehler, 2006; Unwin, 2007) we

would like to argue for curriculum development to be a team-based activity.

Although this is certainly not a new idea, like many campus-based institutions,

lecturers in most departments at Rhodes University work in isolation from

their colleagues when developing their courses, resulting in academic processes

at this institution still resembling a cottage industry where all the major

teaching and assessment processes are managed and executed by a single individual

(Daniel, 1997). In cases where curricula are indeed designed by teams of colleagues,

the absence of an educational technologist (or “technology enthusiast”)

may perpetuate the perceived divide between teaching and learning on the one

hand, and technology on the other. It might therefore be worthwhile to promote

the idea that the curriculum design team should also include an educational

technologist (or enthusiast) and other specialists, for example an information

science specialist from the University Library.

Rather than acting primarily as an “instructional designer”

as described earlier, educational technologists have a role to play in identifying

areas of teaching, learning, assessment and evaluation that might benefit

from the use of ICTs and in assisting lecturers to use ICTs in pedagogically

sound ways. “Practitioners require support in moving from individual

development of learning resources and courses towards team-based collaborative

development and re-use within learning communities” (Littlejohn et al.,

2007, 144). The ICT enthusiast “will be there to mediate … the

potential of the technologies with the desired pedagogies. … they will

be able to reduce anxieties and allow the development of confidence within

the learning community with the technologies being used” (Unwin 2007,

302).

In this paper we described the establishment of a professional

learning community within an academic development unit, the purposes of which

were to address both the lack of knowledge and experience of the AD staff

with regard to using ICTs in teaching and learning, as well as to model the

various ways in which lectures can integrate ICTs into the teaching and learning

of their disciplines. Through using technology to teach our course and through

forming the professional learning community we have tried to provide a professional

development experience for lecturers that might help them to develop the kind

of nuanced understandings called for in Mishra and Koehler’s TPCK framework

(2006).

ENDNOTES

1.See also Shephard (2004) on the need for team-based approaches to curriculum development in higher education.

2.Analysis-Design-Development-Implementation-Evaluation plus a “Rapid Prototyping Phase”

3.As Mishra and Koehler (2006, 1026-7) acknowledge, these ideas are not new. They cite, for example, Keating and Evans, 2001; Zhao, 2003, Hughes, 2005 and Neiss, 2005 who have argued similarly.

REFERENCES

Alessi, S.M. and Trollip, S.R. 1991. Computer-Based Instruction:

Methods and Development. Second Edition. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice

Hall.

Barnett, R. 2000. Realizing the university in an age of supercomplexity.

Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University

Press.

Beetham, H., Jones, S., & Gornall, L. (2001). Career Development

of Learning Technology Staff: Scoping Study Final Report. JISC Committee for

Awareness, Liaison and Training Programme, http://sh.plym. ac.uk/eds/effects/jcalt-project.

Boughey, C. 2002. “Naming' Students' Problems: an analysis

of language-related discourses at a South African university”. Teaching

in Higher Education, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 295-307.

Conole, G., White, S., & Oliver, M. (2007). The impact of

e-learning on organisational roles and structures. In G. Conole and M. Oliver.

Contemporary Perspectives in E-learning Research. Routledge.

Czerniewicz, L. and Brown, C. (2006). The virtual Möbius

strip: Access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs)

in higher education in the Western Cape. Cape Town: Centre for Educational

Technology.

Daniel, J.S. 1996. Mega-Universities and Knowledge Media: Technology

Solutions for Higher Education. London: Kogan Page.

Daniel, J.S. 1997. “Why Universities Need Technology Strategies”.

Change. July/August, 11-17.

D’Andrea, V. and Gosling, D. 2005. Improving Teaching

and Learning in Higher Education. A whole institution approach. Berkshire:

Open University Press.

HEQC. 2005. Improving Teaching and Learning Resource. Council

on Higher Education.

Hughes, J. 2005. The role of teacher knowledge and learning

experiences in forming technology-integrated pedagogy. Journal of Technology

and Teacher Education, Vol. 13. No. 2. pp. 277-302.

Keating, T. and Evans, E. 2001. Three computers in the back

of the classroom: Pre-service teachers’ conceptions of technology integration.

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association, Seattle, WA.

Knight, T. and Trowler P. 2001. Departmental Leadership in Higher

Education. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open

University Press.

Kruse, K. and Keil, J. 2000 Technology-Based Training. The Art

and Science of Design, Development, and Delivery. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Latchem, C. 2005. “Failure – the key to understanding

success”. British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 36, No. 4,

pp. 665-667.

Laurillard, D. 2002. Rethinking university teaching, a conversational

framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London: Routledge

Farmer.

Lave, J. and Wenger, E. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate

peripheral learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Littlejohn, A. and Peacock, S. 2003. “From Pioneers to

Partners: The Changing Voices of Staff Developers”. In J. Seale (Ed.).

Learning technologies in transition. From Individual Enthusiasm to Institutional

Implementation. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger.

Littlejohn, A., Cook, J., Campbell, L., Sclater, N., & Davis,

H. (2007). Managing educational resources. In G. Conole & M. Oliver (Eds.),

Contemporary Perspectives in E-learning Research (Open & Flexible Learning)

(1st ed.). Routledge.

May, T. 2001. Social research. Issues, methods and process.

Buckingham: Open University Press.

McNaught, C., & Kennedy, P. (2000). Staff Development at

RMIT: Bottom-Up Work Serviced by Top-Down Investment and Policy. Association

for Learning Technology Journal, 8(1), 4-18.

Mishra, P. and Koehler, M.J. 2006. “Technological Pedagogical

Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge”. Teachers College

Record, Vol. 108, No. 6, pp. 1017-1054.

Morrow, W.E. 2007. Learning to teach in South Africa. Cape Town:

HSRC Press.

Neiss, M.L. 2005. Preparing teachers to tach science and mathematics

with technology: Developing a technology pedagogical content knowledge. Teaching

and Teacher Education, Vol. 21, No. 5. pp 509-523.

Oliver, M. 2002. “What do Learning Technologists do?”.

Innovations in Education and Teaching International, Vol. 39, No 4, pp. 245-252.

Oliver, M. 2003. “Looking Backwards, Looking Forwards:

an Overview, Some Conclusions and an Agenda”. In J. Seale (Ed.). Learning

technology in transition: From Individual Enthusiasm to Institutional Implementation.

Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger.

Postgraduate Diploma in Higher Education Course Guide. 2006.

Academic Development Centre, Rhodes University.

Quinn, L. 2003. “A theoretical framework for professional

development in a South African university”. International Journal for

Academic Development, Vol. 8, No. 1-2, pp. 61-75.

Quinn, L. 2006. A social realist account of the emergence of

a formal academic staff development programme at a South African university.

A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor

of Philosophy, Rhodes University, South Africa.

Quinn, L. and Vorster, J. 2004. “Transforming teachers'

conceptions of teaching and learning in a postgraduate certificate in higher

education and training course”. South African Journal of Higher Education,

Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 364-381.

Salmon, G. (2005). Flying not flapping: a strategic framework

for elearning and pedagogical innovation in higher education institutions.

ALT-J, 13(3), 201-218. doi: 10.1080/09687760500376439.

Shephard, K. 2004. “The Role of Educational Developers

in the Expansion of Educational Technology”. International Journal for

Academic Development, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 67-83.

Shulman, L. S. 1986. “Those who understand: knowledge

growth in teaching”. Educational Researcher, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 4-14.

Smith, J., & Oliver, M. (2000). Academic development: A

framework for embedding learning technology. International Journal for Academic

Development, 5(2), 129-137.

Thorpe, M. (2002). From independent learning to collaborative

learning: new communities of practice in open, distance and distributed learning,

in Lea, M. R., & Nicoll, K. (Eds.). (2002). Distributed Learning: Social

and Cultural Approaches to Practice (p. 131-51). Routledge/Falmer.

Toohey, S. 1999. Designing courses for higher education. Philadelphia,

Pa.: Open University Press.

Unwin, A. 2007. “The professionalism of the higher education

teacher: what’s ICT got to do with it?” Teaching in Higher Education,

Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 295-308.

Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of practice: learning, meaning

and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zhao, Y. (Ed.). 2003. What teachers should know about technology:

Perspectives and practices. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal.

By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles are free to use, with proper attribution, in educational and other non-commercial settings.

Original article at: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu//viewarticle.php?id=860

|